Meta-Methodologies and the DH Methodological Commons: Potential Contribution of Management and Entrepreneurship to DH Skill Development

July 18, 2013, 10:30 | Short Paper, Embassy Regents E

Given that the nature of the research work involves computers and a variety of skills and expertise, Digital Humanities (DH) researchers are working in teams with Humanists, Computer Scientists, other academics, undergraduate and graduate students, computer programmers and developers, librarians and others within their institutions and beyond (Williford et al., 2012). These projects’ scope and scale also requires larger budgets than is typically associated with Humanities research (Siemens, 2009, Siemens et al., 2011a). As a result, Digital Humanists must developed meta-methodological skills, including teamwork and project management, to support the important and necessary methodological and technological ones in order to achieve project success. Programs such as the University of Victoria’s Digital Humanities Summer Institute’s Large Project Management Workshop (www.dhsi.org), MITH’s Digital Humanities Winter Institute (MITH 2012), University of Virginia’s Praxis Program (Scholars' Lab, 2011) and internships with libraries and DH centres (Conway et al. 2010) are contributing to the formal skill development in these meta-methodological areas while DH teams themselves are reflecting on the importance and nature of collaboration skills developed directly through experience (Liu, et al. 2007; Ruecker, et al. 2007; Ruecker, et al. 2008; Siemens, et al. 2010).

While McCarty (2005) articulates a “intellectual and disciplinary map” for DH (118), which has become an important and agreed upon description of the discipline, no corresponding framework of these necessary meta-methodological skills exists that can guide the preparation of Digital Humanists to be as “comfortable writing code as they are managing teams and budgets” (Scholars' Lab 2011), either within a traditional academic post or an alternative academic one (The Praxis Program at the Scholars' Lab 2012). By drawing upon exemplary DH projects which exhibit individual components of this framework, this paper contributes to larger discussions by suggesting those important meta-methodological skills, knowledge and tasks, whose absences may impact a digital project’s success and long-term sustainability. It ties together the many discussions about undergraduate and graduate DH training and education happening simultaneously across many various forums.

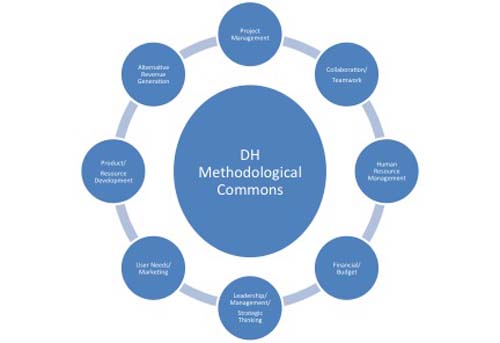

As can be seen in Figure 1, these meta-methodological skills involve more than collaboration and project management skills and include those typically associated with academic entrepreneurship. In their recent report on DH project sustainability, Maron and Loy (2011b) characterize digital resource projects as “small start-up businesses” (32) and use entrepreneurial language, such as empowered leadership, creation of a strong value proposition, cost management, revenue strategies and others to describe the ways in which case study DH projects have managed the impact of the current economic crisis on them. Further, their definition of sustainability, “the ability to generate or gain access to the resources — financial or otherwise — needed to protect and increase the value of the content or service for those who use it” draws further attention to skills, such as management, leadership, budget management, creation of alternative revenue streams, knowledge about users and their needs, and others (Maron, et al. 2011b, 10; Shane 2004). This view has been reinforced in a recent report that reviewed the Digging into Data program. Using the table metaphor, the authors likened project management expertise as the fourth leg, along side data management, domain, and analytical expertise (Williford, et al. 2012). Many digital projects are incorporating aspects of these skills, knowledge and tasks already.

For example, several projects are taking active steps to identify and understand users and their needs and then to ensure that the digital resources address these and allow the user to do more or do it faster or differently than before, while ensuring that knowledge of these resources reach the users (Warwick, et al. 2006; Siemens, et al. 2011b; Ithaka S&R, 2009; Shane 2004; Cohen, et al. 2005). To this end, the LARIAH report (2006) recommends that digital projects consult users widely, often, in a variety of forms and at the different development stages to ensure that a digital resource is in fact used consistently show “a deep understanding and respect for the value their resource contributes to those who use it” (Maron et al., 2009, pg. 7). One way to approach this is have users directly involved in the resource’s development as is the case with TEI-C (nd-b) and Zotero (nd). In other cases, a digital resource can identified new users and extended its services to them, as can be seen with NINES’ move beyond the 19th century to develop a supporting resource for the 18th (18thConnect; Bromley 2011). Alternatively, the digital resource may broaden offerings with new value added services, such as community websites, discussion lists, book and journal distributions and others, in response to users’ requests (Iter 2011). Social media, such as twitter, youtube, and Wikipedia, can also be used to both gather information about users and promote the resource itself. For example, The Modernist Versions project combined an #yearofulysses, webpage, digital version release of Ulysses, and Ulysses Art Competition as a way to generate knowledge (and perhaps even excitement) about the initiative (The Modernist Versions Project). Alternatively, the TEI-C used a viral marketing experiment to understand the size and geographical distribution of its community of practice as it increased awareness of the guidelines (Siemens, et al. 2011b). Digital resource logos embedded in other projects can be important for generating awareness of a resource and its potential uses (TEI-C, nd-a; Zotero). At a basic level, projects must be pro-active in planning effective ways to promote themselves (Guiliano 2012).

As various granting agencies are increasingly prioritizing funding for project development rather than the maintenance and ongoing operations and resource improvements (National Endowment for the Humanities, 2010, Maron et al., 2009), digital projects must develop alternative revenue and funding models that allow them to move from grant funding to “a longer term plan for ongoing growth and development” and to even survive changes in the funding environment (Maron, et al. 2011a, 4; 2011b). These models might include cooperative advertising and click-through ads (Internet Shakespeare Editions, 2010), subscriptions (Iter 2011) and smart phone apps (iHistory Tours 2010b). In order to ensure appropriate levels of resources can be gathered, digital projects must also understand methods to budget the costs need to “cover the costs of the tasks essential to the development, support, maintenance and growth of their projects” (Maron, et al. 2009, 15; Guthrie, et al. 2008; Scholars' Lab, 2011). The latter becomes particularly important since there are expectations that digital resources will continue and be updated and improved with changes in scholarship and technology (Kretzschmar Jr. 2009; Ithaka S&R 2009). Digital projects can then combine both revenue and cost management into long term sustainability plans, often required by funders (National Endowment for the Humanities 2010).

While financial resources are important, long term sustainability and development of digital projects also relies heavily on leadership (Maron, et al. 2011a; Maron, et al. 2009; Shane 2004; Siemens, 2009). These leaders have “a certain passion and tireless attention to setting and achieving goals” (Maron, et al. 2009, 7). This leadership is multifaceted and includes the supervision of human resources, such as paid staff, volunteers and collaborators, and cost and revenue management as well as strategic planning (Ithaka S&R 2009; Shane 2004; National Endowment for the Humanities Office of Digital Humanities 2010). As an example, Transcribe Bentham publishes regular project updates as motivators to its volunteer transcribers (Transcribe Bentham 2011). In addition, these project leaders need to continue to educate colleagues, administration and granting agencies so that these individuals understand the value of DH and the level of support needed for continued growth and development, including financial, in-kind and human resources, recognition and others (Ithaka S&R 2009; Siemens, 2010). The project leader for the 40-year old Thesaurus Linguae Graecae considers “it her job to ‘educate’ current and incoming administrators about her project” (Ithaka S&R 2009, 2). Finally, a strong leader understands when outside expertise and partnerships are necessary to ensure project success (Maron, et al. 2009). The Niagara 1812 iphone app development team included not only writers, researchers, and software developers, but also the nGen-Niagara Interactive media Generator and Brock Business Consulting Group, providing expertise that is not typically available in a History department (iHistory Tours, 2010a).

Figure 1:

Meta-methodological Commons1

Given the nature of digital projects, academics, particularly those from the Humanities, need to adopt these important meta-methodological skills and knowledge in addition to content and methodological ones to ensure project success (Ithaka S&R 2009; Cohen, et al. 2009; Cohen, et al. 2005). By outlining the range of meta-methodological skills, this framework has the potential to strengthen the positive work already ongoing to develop these skills and knowledge and to contribute to the discussion about the important skills that Digital Humanists need to create successful, useful and used projects (LeBlanc 2011; Leon 2011; McCarty 2011; Rovira 2011; Spiro 2011; Cohen, et al. 2005; Scholars' Lab 2011). This paper also contributes to the larger discussion of regarding undergraduate and graduate training and education in Humanities, DH, and beyond and provides a context for thinking about the additional skills needed for both faculty and alternative academic positions (Thaller, et al. 2012; Scholarly Communication Institute 2012; The Praxis Program at the Scholars' Lab 2012; Sample 2012; Pannapacker 2012; Williford, et al. 2012). Finally, it is designed to enable those who work in such teams or who work to support these individuals to recognise and develop the necessary meta-methodological skills and knowledge that lead to project success.

References

Notes

1. The meta-methodological commons is centred around McCarty’s (2005) articulation of the Digital Humanities Methodological Commons.