Bootstrapping Delta: a safety net in open-set authorship attribution

July 18, 2013, 08:30 | Long Paper, Embassy Regents D

Introduction

In non-traditional authorship attribution, the general goal is to link a disputed/anonymous sample with the most probable ‘candidate’. This is what state-of-the-art attribution methods do with ever-growing precision. However, it is similarly important to validate the obtained results, especially when one deals with a faultily-collected or incomplete reference corpus. This is a typical situation of an ‘open’ attribution problem: when the investigated anonymous text might have been written by any contemporary writer, and the attributor has no prior knowledge whether a sample written by a possible candidate is included in the reference corpus. Then the attributor faces the question whether, supposing that all the contemporary writers were represented in the corpus, the results in fact suggest a different person as the most likely author. A vast majority of methods used in stylometry establish a classification of samples and strive to find the nearest neighbors among them. Unfortunately, these techniques of classification are not resistant to a common mis-classification error: any two nearest samples are claimed to be similar, no matter how distant they are.

Given (1) a text of uncertain or anonymous authorship and (2) a comparison corpus of texts by known authors, one can perform a series of similarity tests between each sample and the disputed text. This allows us to establish a ranking list of possible authors, assuming that the sample nearest to the disputed text is stylistically similar, and thus probably written by the same author. However, the calculated distance is usually not followed by an estimation of its reliability. While testing the novel Agnes Gray against a corpus of English novels, one will probably have Anne Brontë as the most likely author. However, testing Emily Brontë’s only novel Wuthering Heights, one is guaranteed to obtain wrong results (because no comparison sample is available), but the ranking of candidates will suggest a most likely author anyway, perhaps another Brontë sister. In a controlled authorship experiment, identifying such a fake candidate is easy, but how can we decide the degree of certainty in a real-life authorship attribution case? Although this problem has been discussed (Burrows, 2002, 2003; Hoover, 2004a; Koppel et al., 2009; Schaalje et al., 2011), we still have no widely-accepted solution. The method introduced below provides a new approach to this problem.

Mater semper certa: Burrows’s Delta

Among a number of machine-learning methods used in stylometry, a special place is occupied by Burrows’s Delta, a rare example of a made-to-measure technique designed particularly for authorship attribution (Burrows, 2002, 2003). Delta is one of the simplest and, at the same time, one of the most effective methods (as evidenced in a benchmark presented by Jockers and Witten, 2008); described in detail, tested, and improved (Hoover, 2004a, 2004b; Argamon, 2008; Smith and Aldridge, 2011; Rybicki and Eder, 2011).

However, despite obvious Delta’s advantages, there are also some drawbacks, shared with a vast majority of state-of-the-art attribution methods. Particularly, Delta relies on an arbitrarily specified number of features to be analyzed. Even if most scholars agree that the best style-markers are the counted frequencies of the most frequent words (MFWs), there still remains the nasty question of the number of words that should be taken into analysis. While some practitioners claim that a small number of function words provide the best results (Mosteller and Wallace, 1964), others prefer longer vectors of MFWs: 100 words (Burrows, 2002), 300 (Smith and Aldrigde, 2011), 500 (Craig and Kinney, 2009), up to even 1,000 or more (Hoover, 2004a). However, a multi-corpus and multi-language study (Rybicki and Eder, 2011) shows that there is no universal vector of MFWs and that the results are strongly dependent on the corpus analyzed.

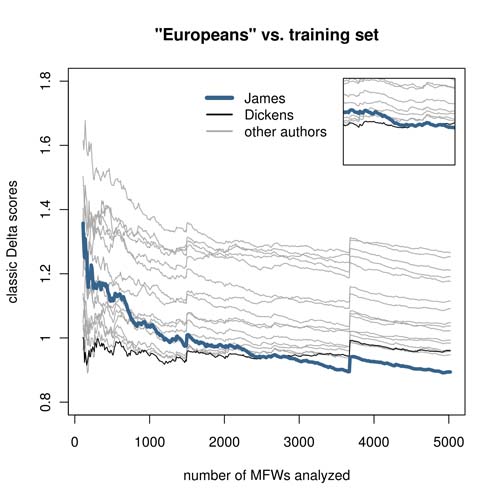

Figure 1.

Who wrote The Europeans? Rankings of 5,000 Delta tests performed on increasing MFW vectors. If the number of MFWs analyzed is lower than 2,700, then Dickens (black thin line) is ranked as the most likely candidate; to get the real author (thick line), one needs to choose a very long vector of words.

What is worse, most attribution techniques, including Delta, allow to measure one vocabulary range (i.e. one vector of MFWs) at once to obtain a ranking of candidates. As shown in Fig. 1, the distances between James’s The Europeans and the members of the training set are unstable and strongly depend on the number of MFWs tested: e.g. one needs to analyze at least 2,700 words to see James ranked as the most likely author of The Europeans instead of Dickens. The danger of cherry-picking is more than obvious here. Although an attributor can perform a series of independent tests with different MFW vectors, a final comparison of thus obtained results is not straightforward at all.

Pater familiae: Bootstrap

In Rudolf Erich Raspe’s collection The Surprising Adventures of Baron Münchhausen, there is a scene where the main character, trapped in a swamp, pulls himself out by his own bootstraps. Although it is still disputed if Münchhausen was pulling by his boots or by his hair, the bootstrapping became a metaphor for statistical methods that make up for absence or unreliability of parameters with intensive resampling of the original population. The bootstrapping procedures are widely used in biometrics and social sciences, and their idea is quite simple: in a large number of trials, samples from the original population are chosen randomly (with replacement), and this chosen subset is analyzed in substitution of the original population (Good, 2006).

When Delta meets Bootstrap

The aim of the technique presented below is to overcome the disadvantages of the existing nearest neighbor classifications. It has been based on Delta and extended with the concept of bootstrap. The method relies on the author’s empirical observation that the distance between samples similar to each other is quite stable despite different vectors of MFWs tested, while the distance between heterogeneous samples often displays some unsteadiness depending on the number of MFWs analyzed.

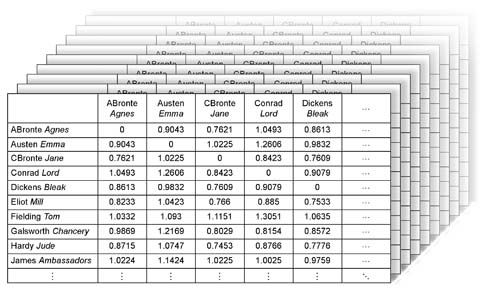

The core of the procedure is to perform a series of attribution tests in 1,000 iterations, where the number of MFWs to be analyzed is chosen randomly (e.g., 334, 638, 72, 201, 904, 145, 134, 762, …); in each iteration, the nearest neighbor classification is performed. It could be compared to taking 1,000 photos from different points of view. Thus, instead of dealing with one table of calculated distances — as in classic Delta — one obtains 1,000 distance tables. Next, the tables are arranged in a large three-dimensional table-of-tables, as visualized in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Results of 1,000 bootstrap iterations (tables of distances between texts samples) arranged in a three-dimensional table.

The next stage is to estimate the mean and standard deviation of each cell across 1,000 layers of the composite table. This is a crucial point of the whole procedure. While classical nearest neighbor classifications rely on point estimation (i.e. the distance between two samples is always represented by a single numeric value), the new technique introduces the concept of confidence interval. Namely, the distance between two samples is a range of values represented by the mean of 1,000 bootstrap trials plus 1.64σij below and 1.64σij above the arithmetic mean.

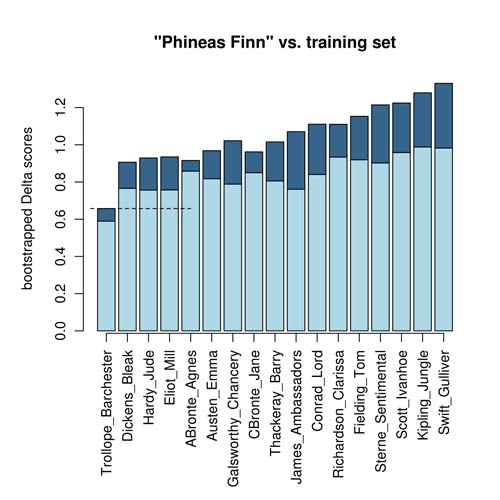

Figure 3.

Who wrote Phineas Finn? Ranking of candidates using confidence intervals.

An exemplary ranking of candidates is shown in Fig. 3. The most likely author of Phineas Finn is Trollope (as expected), and the calculated confidence interval does not overlap with any other range of uncertainty. This means that Trollope will be ranked first with a 100% probability.

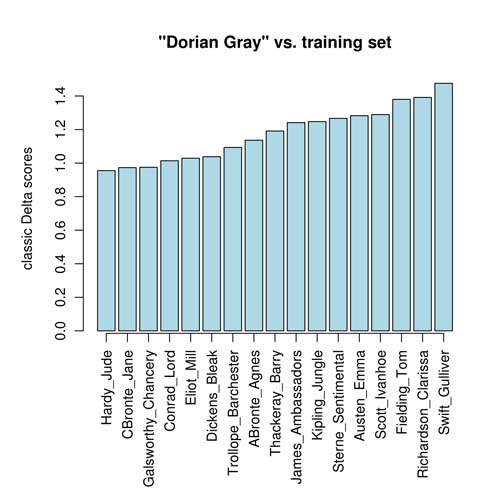

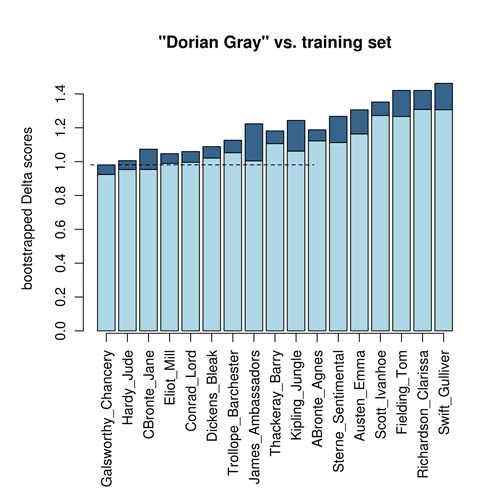

The real strength of the method, however, is evidenced in Fig. 4 and 5, where The Portrait of Dorian Gray is tested against a training set which does not contain samples of Wilde. Classic Delta simply ranks the candidates, Hardy being the first (Fig. 4), while in the new technique, confidence intervals of the first three candidates partially overlap with each other. In consequence, the assumed probability of authorship of Dorian Gray is shared between Galsworthy (54.2%), Hardy (34.8%) and Charlotte Brontë (11%). The ambiguous probabilities strongly indicate fake candidates in an open-set attribution case.

Figure 4.

Who wrote The Portrait of Dorian Gray? Ranking of candidates using classic Delta procedure (500 MFWs tested).

Figure 5.

Who wrote The Portrait of Dorian Gray? Ranking of candidates using confidence intervals.

First benchmark

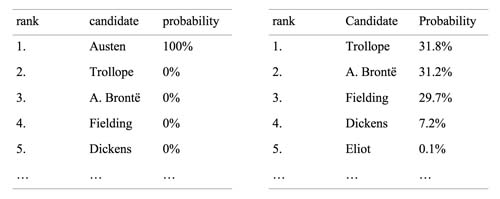

The first exemplary results of two attribution experiments are shown in Table 1. In both approaches, Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility was assumed to be an ‘anonymous’ sample to be attributed, and the comparison corpus consisted of 17 texts by known authors. In the first experiment, the behavior of 1,000 single bootstrap trials led to the final ranking with Jane Austen as the only probable candidate (as expected). In the second experiment, Austen’s sample was excluded from the comparison corpus, so that the real author could not be guessed. However, the method refused to point out a most likely candidate with a high probability. As one can see, there is uncertainty about the first three candidates.

Table 1.

Who wrote Sense and Sensibility? A ranking of candidates: (1) where the real author (Jane Austen) is available in the comparison corpus (left); and (2) where the comparison corpus does not contain samples by the real author (right).

The procedure presented above, displays an accuracy comparable to the state-of-the-art methods used in stylometry, but it is far more sensitive to fake candidates. While the existing methods provide two possible answers to the problem of attribution: X is the author or X is not the author, the procedure proposed introduces a third answer: unclear results, an important safety net against false attribution.