Epistolary voices. The case of Elisabeth Wolff and Agatha Deken

July 18, 2013, 10:30 | Long Paper, Embassy Regents D

The Question

In his book Computation into criticism John Burrows analyzed the speech of 44 different characters from novels by Jane Austen using the 30 most frequent function words (Burrows 1987). He showed how even this small amount of high frequency words yielded clearly distinctive results for Austen’s different characters, more so than the characters in novels written by other authors from Austen’s time or from a later time period. Recently, John Burrows and Hugh Craig applied multivariate analysis to the speech of characters in a corpus of seventeenth-century plays (Burrows & Craig 2012). They showed that characters can be distinguished in this way, but that the characters of one playwright usually cluster together compared to the characters of another playwright. In their research, stylometric analysis and authorship distinction are nicely intertwined.

The assumption behind their research seems to be that it is a natural wish of a literary author to make his or her characters speak thus on paper or on stage as one would expect of a character of that gender, age, social background, etc. But is this true? Could it be based on anachronistic expectations, based on our own horizon of experience? Or is it indeed to be seen as a universal characteristic of all kinds of fiction from all time periods and all cultures?

This assumption should be tested on other (historical) genres. In this contribution I want to find out whether the fictional letter writers in the epistolary novels of two famous Dutch women writers show a significant stylistic differentiation. The case also involves an authorship problem.

The Case

Elisabeth Wolff-Bekker (1738-1804) and Agatha Deken (1741-1804) met in 1776 and immediately became great friends. When Wolff's husband died in 1777, Agatha moved in with Elisabeth and from then on, they closely collaborated on many publications, most important of which are their epistolary novels (Buijnsters 1984). The first one, The history of Sara Burgerhart, was published in 1782 and was an immediate bestseller. It was followed by The history of Willem Leevend, a much larger and more complex epistolary novel, published in 1784-1785. The one was The history of Cornelia Wildschut, almost as long and certainly as complex as their Willem Leevend and published in 1793-1796. Much has been written about the two women and their work. Wolff is known to have been a highly educated and very smart and lively woman, whereas Deken, raised in an orphanage, is described as timid and dull. Based on these impressions, many readers and scholars assume that Wolff was responsible for the lively and funny letters (and/or letter writers), and Deken for the dull and simple letters (and/or letter writers). Even during their lifetime, this seems to have been the general idea. In their forewords and in some personal letters they explicitly stated that this was ridiculous: they did everything in close collaboration. Near the end of her life, Deken states she would like to draw up a list of the fictional letters she wrote, to prove these naïve assumptions wrong. She never got around to doing that. Can we, by using stylometric methods, establish how they distributed the work load between them?

The three epistolary novels mentioned above are digitally available at www.dbnl.org. They will be compared to three other epistolary novels that are available in digital form in the same digital library: Het land, in brieven written by Elisabeth Maria Post and published in 1792; Charakters en lotgevallen van Adelson, Héloïse en Elius by Anna Catherina van Streek-Brinkman (1804); and De kleine pligten by Margaretha Jacoba de Neufville (1824-1827). Finally, the fictional letters will be compared with a digitally available corpus of personal letters written by Deken and Wolff, based on the editions of Dyserinck (1904) and Buijnsters (1987).

The Results

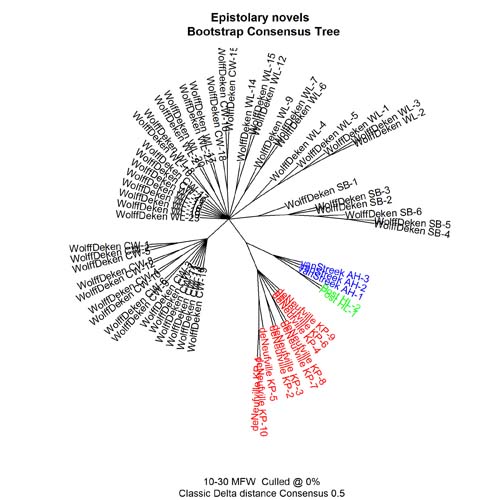

We start with an overview, comparing all six epistolary novels with each other. I made use of the stylometric R-script developed by Eder and Rybicki, which performs Principal Components Analysis, Cluster Analysis, Multidimensional Scaling, and Bootstrap Consensus Trees (Eder & Rybicki 2011), choosing the last of these for my analysis since the bootstrap consensus tree is a harmonisation of as many different cluster analysis based on word frequencies as the scholar indicates. The six novels are diverse in length, with a maximum of 585,664 tokens and a minumum of 59,752. In Fig. 1 they have been analyzed in samples of 25,000 tokens.

Fig. 1: Epistolary novels

The three Wolff & Deken novels are clearly separated from the novels by the three other (single) authors. This shows that co-authors Wolff and Deken have a distinctive style compared to the other three. A comparable picture arises when we analyse the text of the 30 main characters from all six novels, all having more than 17,000 tokens in their individual corpus.

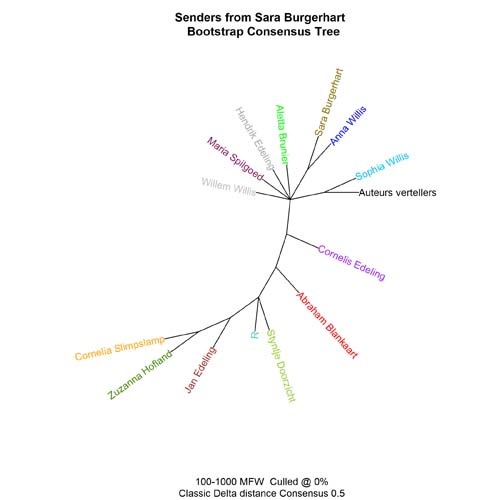

In the next step we zoom in on one of the Wolff & Deken epistolary novels to find out if the letter writers can be distinguished, and additionally, if the letter writers clearly fall into two different clusters which could be linked to the two different authors. This will be done on their first joint publication, Sara Burgerhart, published six years after they met. This epistolary novel has letters and some other texts presumably written by 26 different characters, including one Anonymous and also text written by the authors/narrators. Fifteen of these have a corpus of tokens higher than 2,000 (including the authors/narrators). Fig. 2 shows that the different characters are indeed distinguishable when their complete corpora are analyzed.

Fig. 2: Senders from Sara Burgerhart (no sampling)

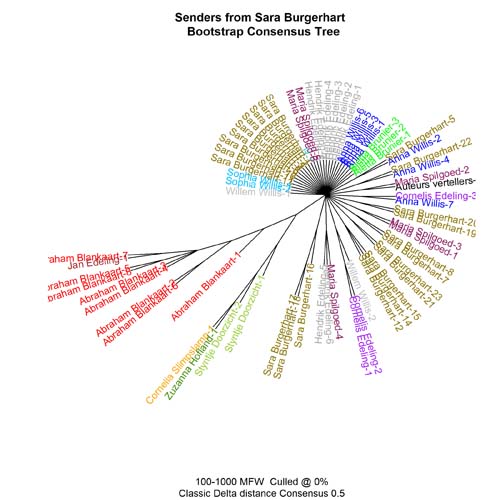

Since the authors/narrators’ text (Forewords and Afterwords) in Wolff & Deken’s novels is usually undersigned by Wolff only, this consensus tree may show a certain work distribution between the two women. Wolff’s style may be prevalent in the letters attributed to the main characters Sara Burgerhart, her women friends Aletta and Anna, and her husband-to-be Hendrik. Through extrapolation, Deken then could be responsible for some of the bad characters in the novel, such as Cornelia Slimpslamp, and Zuzanna Hofland. She could also be the ghostwriter of pious Styntje Doorzicht. And she would indeed be very lively and funny in her letters by Abraham Blankaart. But it is too soon to conclude this; when we use sampling (2,000 tokens), the picture is rudely disturbed and no clear distinction can be found (Fig. 3). Many of the samples are directly connected to the root, which means the software could not convincingly cluster them to any other sample. The only significant branch occurs for the samples of the character Abraham Blankaart, which suggests his letters have a clearly individual style.

Fig. 3: Senders from Sara Burgerhart (sampling)

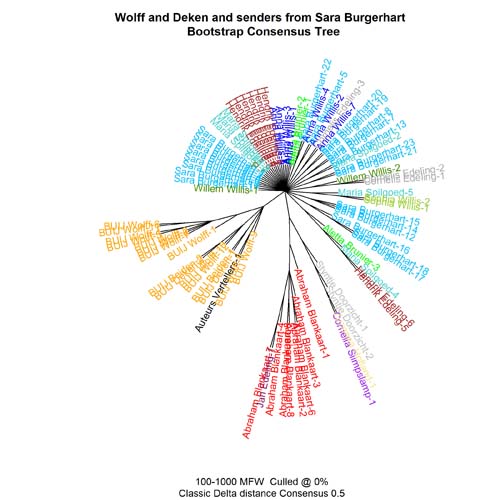

The implication is that Wolff and Deken either both worked on the same letters, revising each others’ work all along, or that their style of writing is so much alike that they cannot be distinguished. The first option is difficult to prove; historical evidence is not available to confirm this. The second option can be explored by a comparison of the letters in the epistolary novels to the personal letters of Deken and Wolff from the time period in which they wrote and published Sara Burgerhart (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Wolff and Deken and senders from Sara Burgerhart

Fig. 4 has three additional corpora in the comparison, from the years 1776-1782. Eleven letters written by Deken, 4,594 tokens in total; 35 letters written by Wolff, 25,790 tokens in total; and twelve letters that were written jointly, 5,878 tokens in total. The consensus tree again shows no clear distinction pointing to two clearly different authors. And, again, the letters of Abraham Blankaart show up as a rather distinctive set.

Conclusion

The measurements seem to imply that the writing styles of Deken and Wolff in their epistolary novels were very much alike. This confirms their own statements about their collaboration, and can be explained by their close working relation: they not only wrote the works together, but they were very close friends, even living together.

As to the other question I started out with, the style of different characters, something extraordinary showed up in the graphs. Only one of the main characters of Sara Burgerhart clearly had a more individual style than the other main characters, namely Abraham Blankaart. So for now, it seems that a distinctive style for all characters such as John Burrows has shown for the characters of Jane Austen, is not a prerequisite for these epistolary novels or these authors. Still, when reading these novels we do recognize the letter writers. Further research, e.g. with Burrows’s Zeta, is needed to find out how the authors exactly did this. This is not the end of what we have to do, however: we also should continue research into the genre of epistolary novels in other languages and time periods, to find out whether stylistic characterization occurs elsewhere in the genre, or whether the aimiable character of Abraham Blankaart is indeed a clear exception.