Agents for Actors: A Digital Humanities framework for distributed microservices for text linking and visualization

July 19, 2013, 08:30 | Long Paper, Burnett 115

The Scene

A raucous party on the eve of the Battle of Bosworth field in 1485, wine flows by the gallon, the table bends under the weight of the meat and breadcrumbs fly across the table as Richard III rises painfully to address his loyal peers:

(transcription of the audio recording (British Broadcasting Corporation 2009), checked against (Curtis 2001)).Now is the summer of our sweet content,Made overcast winter by these Tudor clouds.And I that am not shaped for black-faced war,I that am rudely cast and want true majesty,Am forced to fight, To set sweet England free.I pray to Heaven we fare well,And all who fight us go to Hell

Thus starts Rowan Atkinson’s fabulously funny alternate history of Britain, the History of the Black Adder (Atkinson et al. 1983), one of the hallmark BBC sitcoms of the 1980s.

Fast forward through the show, right to the closing credits: “Written by Richard Curtis and Rowan Atkinson with additional dialogue by William Shakespeare”. And, indeed, even Richard III’s short speech contains at least three near-verbatim citations from Shakespeare’s play of the same name (and actually a fourth and a fifth, but more on that later):

Now is the Winter of our DiscontentMade glorious Summer by this Son of Yorke: […]But I, that am not shap'd for sportiue trickes, […]I, that am Rudely stampt, and want loues Maiesty, […]And that so lamely and vnfashionable,That dogges barke at me, as I halt by them [1]

All would be good if the citations were indeed verbatim, but they are not — the wit of Richard’s speech and indeed of much of Blackadder’s attraction depends on twisting citations, creating tension between original and new wordings. Blackadder like much of postmodern British Sitcom consciously sees history as a “cluttered patchwork of questionable stories which have been re-written, re-evaluated and ridiculed“ ((Roberts 2012), pos. 26, Kindle edition), using allusions precisely to enhance the sense of a subjective, patchwork-like history.

Enter Agents for Actors

Agents for Actors (AfA) (https://github.com/mwkuster/agents-for-actors) is an experimental, LGPL-licensed Open Source “framework for distributed microservices for text linking and visualization” that the author has developed to calculate precisely the types of “twisted” citations that we are seeing. It takes some inspiration from W. Artes’ Bachelor thesis (Artes 2012) on Similarity Search (cf. also (Hedges et al. 2012)), that the author has supervised, especially on the choice of NGram models for comparison, but is an independent implementation that deviates in the way the NGram model is built (cf. below). AfA is linked to TextGrid’s Text-Text-Image-Link Editor (Selig, Küster, and Conner 2012).

Afa identifies allusions between texts and their presumed sources and gives exact provenance information as XPointers (Küster et al. 2011). As an additional spin we make the comparison of Black Adder’s modern orthography transcript against the original-spelling First Folio, transcribed by Trevor Howard-Hill (http://ota.ox.ac.uk/id/3014).

AfA is extendable to other similarity models and measures and could be adapted for new visualization frontends. Given the computational complexity it embraces multicore architectures and parallelizes computations wherever possible. AfA situates itself between the macro-vision of big data digital humanities (e.g. (Jockers 2012) and the forthcoming (Jockers 2013)) and the micro-vision of the classical, manually encoded critical apparatus.

Implementation

AfA is implemented in the functional language Clojure (Hickey 2010) (Emerick, Carper, and Grand 2012; Halloway and Bedra 2012) on top of the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Clojure thrives on immutable functional data structures (Okasaki 1999) for heavily multithreaded applications. Mutable operations are largely under control of Clojure’s Software Transactional Memory (STM).

AfA uses two Clojure paradigms to parallelize activities:

- Futures: non-blocking threads that are transparently managed to parallelize calculations

- Agents: asynchronous, used to interact with the visualization layer

The code basis itself consists of a number of individual functions for interacting with files, calculating similarity measures, handling visualization etc. They can be regrouped flexibly.

Handling XML

AfA currently expects both source and target to be encoded in XML. Both therefore contain parts such as the TEI header, cast lists or stage directions that without filtering generate noise when searching for references. Still, we need to preserve the exact pointers to source and target fragments in the underlying XML files to guarantee traceability.

With mutable data structures this objective would be difficult to attain without costly copying operations of XML structures in memory. The immutable abstraction of Zippers (Huet 1997) offers a solution by having the XML structures only once in memory, the algorithm operating on pointers to individual elements (“locations”). Furthermore, unlike e.g. XML DOMs Zippers are generic abstractions for tree structures, not only XML. AfA can hence be adapted to any form of structured data sources.

Measuring similarity

The AfA framework allows for multiple models and measures. At is simplest, the comparison is done using NGram models (cf. (Manning and Schuetze 1999)), that are used for fuzzy text comparison, e.g. in (Kestemont, Daelemans, and De Pauw 2010) and (Bernholz and Pytlik Zillig 2011), not to mention in Google-style big-data (Google 2010).

The tests presented in this paper are done with a variation of the NGram model, combining NGrams of words, that move in a slider over the text, creating chunks of size C, with NGrams of letters for the actual comparison of those chunks.

In the following example C=5. This way, the phrase “Now is the summer of our sweet content” into four chunks of five words each:

Each of these chunks is compared with a chunk from the supposed source material, built with the same algorithm, so that the totality of compared chunks is the Cartesian product NxM, N being the number of chunks in the source and M that in the target. Each of these pairs of chunks is compared using an NGram of ngram-count characters to smoothen over differences in spelling. The respective confidence level for a hit is calculated using the maximum dice-coefficient (cf. (Manning and Schuetze 1999), table 8.7) applied to this combination of chunks: (apply max (map (fn [[t1 t2]] (dice-coefficient (ngrams ngram-count t1) (ngrams ngram-count t2))) (for [chunk1 chunk-seq1 chunk2 chunk-seq2] [chunk1 chunk2]))) The algorithm works for other measures returning similarities normalized to [0,1].

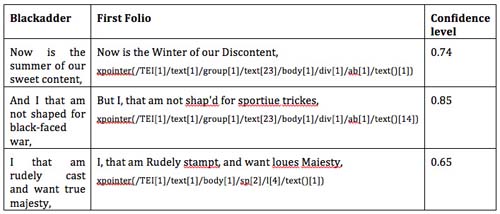

Applying this admittedly computationally expensive algorithm to Richard’s speech with C=6, N=4 and a minimum confidence level of 0.65 identifies in Shakespeare’s complete First Folio precisely the expected links (XPointers referring to http://ota.ox.ac.uk/id/3014):

The algorithm cannot identify the fourth allusion, though, that contrasts the concepts of “overcast winter” with “glorious Summer”.

Dressing up

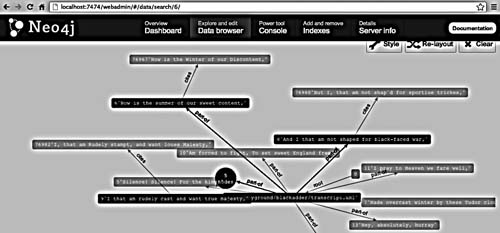

For visualization AfA uses Neo4j, an increasingly popular Open Source Non-SQL graph database (Neo4j.org 2012). Neo4j centres around two Topic Map (ISO/IEC 2002) like concepts, nodes and relationships. Both have unique identifiers and can have arbitrary properties besides. Relationships must have a start and an end node.

With neocons (Klishin 2012) Neo4j has an intuitive Clojure interface that permits to store and query the graph. Neo4j’s admin interface also has one of the more innovative graph UIs available in an off-the-shelf database.

Intertextuality and a bit of theory

This screenshot shows the individual phrases of Richard’s speech in Blackadder with their links to their source (“part-of”) and the phrases they cite (“cites”), giving a good visualization of the intertextuality (Kristeva 1969) (Barthes and Marty 1980; Barthes 1968) (Allen 2011) that animates much of Atkinson’s comedy.

Note that AfA does not “interprete” the links. Statistical methods rarely have an obvious interpretation, their epistemological openness and continuity being an asset for postmodern texts in a world of “stylistic and discursive heterogeneity without a norm” (Jameson 1991). If anything, Genette’s theory of hypertextualité (Genette 1982) might give us an adequate terminological apparatus.

Outlook

Three of the citations in Richard’s speech AfA has identified for us, the fourth we have discussed — but there is a fifth. Films are more than dialogue; intertextuality can just as well be construed without words. When Atkinson’s Richard is halfway through his speech we hear a dog barking — Richard is so ugly that “dogges barke at me”. Also, there is open linked data out there that situates Blackadder in context, here linking manually to Freebase movie data with some of Atkinson’s other films (for handling Freebase data cf. (Redmond and Wilson 2012), chapter Neo4j/Big data):

In the end an approach focussed on a narrow understanding of intertextuality will not suffice for audiovisual media; it must evolve into a network including knowledge and symbols (Peirce 1998), contextual, textual and non-textual. Now we can only manually add nodes establish these links, but there may be another untold history ahead.

References

Notes

1. The Tragedy of Richard the Third, cited after Shakespeare’s First Folio as transcribed in http://ota.ox.ac.uk/id/3014