Word-level Language Identification in “The Chymistry of Isaac Newton“

July 18, 2013, 13:30 | Long Paper, Embassy Regents C

Introduction

Language Identification is the task of determining the language of short text snippets, much shorter than for e.g., text classification. In Computational Linguistics (CL), language identification is generally considered a solved problem—but these methods assume that a text is monolingual, and at least 100 characters long. Furthermore, such methods cannot be used for multilingual texts in which the author switches between languages within a sentence, as in the “Chymistry of Isaac Newton” (Walsh and Hooper 2012), a collection of 119 alchemical manuscripts written by Newton over a 30-40 year period beginning in the mid-1660s. The team behind The Chymistry of Isaac Newton Project at Indiana University has transcribed these manuscripts and is publishing a digital scholarly edition at www.chymistry.org. Attempts to automatically analyze this corpus, even with basic levels like POS markup and lemmatization, are difficult because Newton frequently switches between English, Latin, and French within a paragraph or sentence, as shown in the following sentence: “The short lived & despicable plant [[LAT Paronychia folio Rutaceo [[ENG infused in beer, doth wonders in curing the kings evill.” For this reason, we developed a new method for automatically identifying the language for single words rather than for complete texts. This method requires more information because the classification is finer-grained than standard methods, which have access to more text.

There is an additional complication because seventeenth-century English and French allowed many spelling variations, unlike Latin, which was fairly standardized.

We first train and test the method on the corpus itself. However, since this corpus is rather small for methods developed in CL, we also investigate whether the method can use either current texts or texts written by Newton’s contemporaries. While this approach increases the amount of training data, it is unclear whether the additional data is useful given that all these additional Newton-era and modern texts are monolingual, and that the modern English texts will fail to exhibit the large variations in spelling that we see in Newton’s manuscripts. Our experiments show that using Newton’s own texts reaches the highest accuracy of close to 90%, but using modern text results only in a moderate decrease of 2% points.

Language Identification on the Document Level

All previous work in language identification assumes that each text to be identified is written in a single language. For this task, naïve approaches are often utilized with high success. The simplest methods use the presence of language-specific characters in a text to identify the language. Another method uses lists of the most common words of a language (Johnson 1993). Then, the text is classified based on which set of common words occurs most frequently.

Cavnar and Trenkle (1994) use the same method with relative frequencies of n-grams rather than words and reach an accuracy of 99.8% given texts with at least 400 n-grams.

Our work is based on work by Beesley (1988) and Mandl et al. (2006), who also extract n-grams. Beesley determines language identity for a whole text of any size by comparing probabilities of bigrams and characters of the individual words for each candidate language and labeling the text as the language most probable for the most words. Mandl et al. use n-grams to determine switch points between languages. Recent approaches use more sophisticated methods, such as vector-space models (Prager 1999) or multiple linear regression (Murthi and Kumar 2006). However, those approaches are difficult to use on the word level.

The Data Source

The Newton Alchemical Corpus. The Newton alchemical corpus comprises approximately 850,000 words, drawn from a three-language lexicon of 23,000 unique wordforms. Newton frequently alternates between English, Latin, and French. The collection contains documents written exclusively in either English or Latin. These documents were used as training data for our approach.

For both English and Latin, texts of approximately 70,000 words were used as training data. Additionally, a list of words was extracted from each monolingual training set and used as a lexicon for that language. French only occurs in the multilingual documents and much more rarely than English or Latin in these documents. Since there are no documents written exclusively in French, no French training data was available from this source.

Non-alphabetic elements (e.g., punctuation and numbers) are automatically labeled as non-words. Additionally, the texts include recipes, calculations and figures, and thus contain a large number of alphabetical variables and labels. These items are not relevant for language identification and present potential obstacles for automatic approaches. Thus, they were excluded from training/testing. Any string of letters not containing a vowel was determined to be a non-word.

For testing, we selected six texts (126,000 words) that contained a high degree of switches between languages and annotated them manually for the languages used. Three texts (20,000 words) were used for optimizing parameters, and three more texts (106,000 words) for testing. Note that the test set does not contain any French words.

Other texts: For English texts from Newton's era, we used excerpts of Francis Bacon's The New Atlantis (1627) and Essayes or Counsels, Civill and Morall (1625) and Robert Boyle's The Sceptical Chemist (1661) and Experiments and Considerations Touching Colours (1664). Newton-era Latin texts were excerpted from Rene Descartes' Meditationes de prima philosophia (1641), Benedict de Spinoza's Ethica (1677), and Carl Von Linne's Species Plantarum (1753).

The modern day training set for English was extracted from The Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post stories from 2006.

Word-Based Language Identification: The Newton Corpus

Our approach assumes that a particular document to be identified contains one or more of the languages used in the corpus: English, Latin, and French.

We automatically segment the texts into words, extract all n-grams per word, and calculate the relative frequencies of the n-grams in each language (normalized for capitalization). Figure 1 illustrates this process for the Latin word “ignis”.

Figure 1:

Extraction of bigrams (left) and comparison of relative frequencies. $ and # mark word boundaries.

We determine a language score by averaging over all n-gram probabilities of a word. Since there is no training data for French, we use only English and Latin for training, with a threshold: First, the scores for English and Latin are determined. If neither the English nor the Latin probability exceeds a pre-determined threshold, the word is determined to be French. This corresponds to the intuition that if the n-grams of a word are rare in both English and Latin, then that word is unlikely to be from those languages but from a different language. The final decision also takes the language label of the previous word into account. If the current word is in the lexicon of the language of the previous word, the current word is tagged as that language. If the word is not in the lexicon, we consider the language identity probabilities of the previous word by adding a proportion of that probability to the probability that the current word is English, and do the same for Latin. This decision captures the tendency of words to belong to the same language as the words in the immediate context, while allowing for the possibility of switches. At the beginning of a sentence, the threshold is higher than between words.

Performance on the current language identification task is defined as accuracy: the percentage of words in the test texts (excluding non-words) with correct language labels.

Ultimately, we found 5-grams to be the best performing setting.

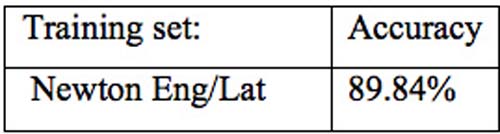

The results in table 1 show that we reach an accuracy of 89.84%. This is lower than the results reported for language identification on full documents, but the task is more difficult. The word misclassified most often is a genuinely ambiguous word, “in”. In general, the words most frequently misclassified are short (2-3 characters).

Word-Based Language Identification: Using Other Corpora for Training

Since the training set from the Newton corpus is rather small, we also investigated using either training texts from Newton’s era, or modern corpora. As no modern Latin is available, we used the Newton-era Latin texts.

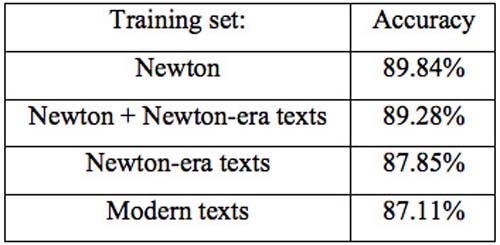

The results in table 2 show that using the small set of texts by Newton gives the highest accuracy. Adding Newton-era texts does not result in the expected increase in accuracy. Instead, accuracy decreases minimally from 89.84% to 89.28%. Using only Newton-era texts decreases accuracy by approximately 2%. Using modern texts also results in a small decrease in accuracy. However, our method does not suffer much from using modern texts, which suggests that the information about character differences between languages does not heavily depend on the changes in spelling.

Conclusion

We presented a novel method for identifying language on individual words in multilingual texts. We have shown that the method reaches an accuracy of 89.84% when trained on monolingual texts from the same author. However, if no such texts are available, other texts from the same era, or even current texts can be used with only a minor degradation in performance.