Extraction and Analysis of Character Interaction Networks From Plays and Movies

July 18, 2013, 13:30 | Long Paper, Embassy Regents D

1. Introduction

Due to recent efforts to digitize literary works, researchers have been able to perform meaningful large-scale analyses of millions of texts and reach meaningful conclusions about literature, language, and culture using statistical analysis. This approach is powerful, but frequently ignores subtleties in literary works, reducing complex texts to bags of words. Literary theorists take a different approach, performing in-depth qualitative studies examining plot intricacies and character interactions. Unfortunately, such deep analysis does not scale well due to human time constraints.

In our project we combine these two approaches to literary analysis, allowing us to benefit from the advantages of both. More specifically, we develop and apply methods for automatically extracting character interaction networks from works of entertainment and use properties of the resulting networks to draw conclusions about these works.

There are three main components:

- (1) Extracting character interaction networks as weighted graphs, with characters as nodes and interaction scores as edges

- (2) Computing informative properties (e.g., clustering coefficient) of the resulting networks

- (3) Using those properties to answer broad questions about the works (e.g., whether different media types are characterized by distinctive interaction networks) by constructing machine learning classifiers.

2. Related work

As mentioned earlier, most computational literary analysis has been at the word level. There are, however, several exceptions. Most notably, Elson et al. (Elson et al. 2010) effectively utilized dialogue interactions in sixty 19th century literary works to form social networks and make interesting discoveries about a particular genre. Other researchers used network theory to analyze small groups of texts, such as Hamlet (Moretti 2011), Greek tragedies (Rydberg-Cox 2011), Shakespeare (Stiller and Hudson 2011), and Marvel comics (Alberich et al. 2002). These studies were all relatively narrow in focus, leading to valuable discoveries about a small number of texts. More recently, C.-Y. Weng et al. (Weng et al. 2009) proposed a network extraction method for movies and T.V. shows based on co-occurrence, successfully identifying lead roles and other attributes for several movies.

Overall, previous work primarily focused on using character interaction networks to improve understanding of individual texts or movies. We feel humans already do a very good job—better than computers—of analyzing small collections of works; our main limitation is insufficient brainpower to simultaneously analyze and compare hundreds or thousands of works. As such, we are interested in conducting a large-scale study of character interaction networks for diverse works of entertainment. Our goal is not to examine literature from a specific time period or a particular film’s plot, but rather to discover sweeping trends in literature and movies across genres and over time.

3. Methodology

3.1 Building Networks

We focused on play and movie scripts because their structured format is well suited for systematically detecting interactions between characters. We obtained scripts and relevant metadata from a variety of sources (Internet Movie Script Database (2011); Project Gutenberg (2011); The Complete Works of Shakespeare (2011); EOneill.com EText Archive (1999); Read Plays Online-Read Print (2011); The EServer Drama Collection (2011); Rotten Tomatoes (2011); Robnik-Sikonja and Kononenko (1997), automating the process with Python scripts. For consistency, we then converted all data into a standardized intermediate format using more regular expressions, and a blacklist of non-verbal action commands (e.g. “fade in”). In total, we extracted 173 plays and 580 movie scripts.

We experimented with four extraction algorithms for constructing character interaction networks. Our first approach, used by Weng et al. (Weng et al. 2009), defined the interaction score for two characters as the number of scenes in which both appear. Our second algorithm extended this concept, incorporating the number of lines spoken in each scene. Unfortunately, many scripts had long scenes, resulting in falsely high interaction scores between two characters in different parts of the same scene.

We then used what we call the Closeness approach to consider an interaction to have occurred between two characters only when they have spoken nearby lines in the same scene, increasing their scores by an amount linearly decreasing with increased distance. Our fourth and final algorithm weights interactions by the total number of words exchanged.

3.2 Property Calculation

For each character interaction network, we computed the following network properties, which represent different concepts in literary works:

- Average clustering coefficient: how much groups of characters tend to cluster together

- Single character and relationship centrality: how much the work focuses on a single character above all others

- Single relationship centrality: how much the work focuses on a single relationship between characters above all others

- Top character weight variance: whether the group has a large group of similarly prominent characters or a few main characters and many less important roles

- Top relationship strength variance: whether relationships are emphasized roughly equally, or if there is an emphasis on a select few

- Entropy of node degrees and edge weights: an alternate approach to quantifying the spread in the distribution of character and relationship importance

- Mean and variance of top character relationship strengths: whether the work has one or several main storylines

- Percentage of existing edges: an alternate approach to determining number of storylines

- Betweenness centrality — maximum, difference, and entropy: another alternate method of determining the relative importance of main characters

- Number of characters: used as a final feature in our classifiers

3.3 Classification

We used our network properties as features in binary classifiers for various media aspects:

- Media type: plays or movies

- Date of movie: before or after 2000

- Date of play: before or after 1800

- MPAA rating

- Audience and critic ratings

- Single genre (e.g. romance or not)

- Between genres (e.g. romance or horror)

- Author (e.g. Shakespeare or George Bernard Shaw)

We experimented with logistic regression classifiers and decision trees, because these classifier types easily allowed us to understand how features were being used to arrive at predictions. We used the Orange library for Python, normalized our features, used k-fold cross validation to test our classifiers, and used the Relief algorithm [14] for top feature selection.

Because two classification classes did not always have the same number of examples, classification accuracies were sometimes misleadingly high even for poor classifiers. Thus we used area under the curve (AUC) as our primary performance metric.

4. Results

We found logistic regression to have higher AUC’s for 26 of our 35 classification tasks. Of the remaining 9 tasks, 8 performed relatively poorly on both classifiers (AUC < 0.65). Decision trees had consistently high AUC’s (0.8-0.9) on training data, suggesting overfitting despite our parameter selection efforts. The logistic regression classifiers did not suffer from this problem, so we focused on logistic regression results and used decision trees as means of gaining intuition for the role of certain features in the classification step.

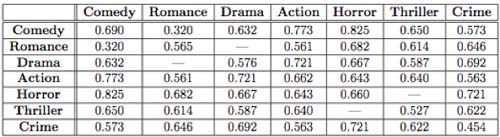

Table 1: Logistic regression classifier AUCs for various classification tasks

Table 2: Logistic regression classifier AUCs for genre-related classification tasks

Our results are shown in the above tables. Dashes indicate insufficient data for proper classification.

5. Analysis

5.1 Media type classifier

We were very successful in classifying plays versus movies. We found that plays are characterized by high top character relationships, high single character centrality, and low top character weight variance relative to movies, suggesting that plays tend to have a clear-cut main character with several important supporting characters that interact primarily with the main character. A classic example is Hamlet, as can be observed by its interaction graph:

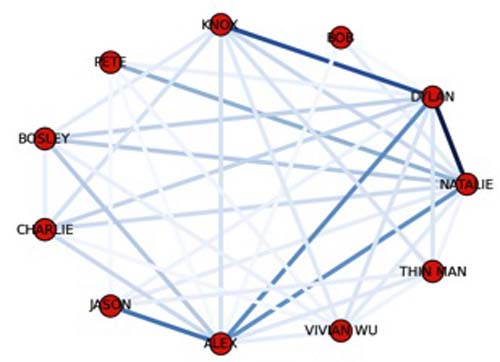

Results for movies suggest they tend to have several main characters, as in Charlie’s Angels:

5.2 Play date classifier

Important features from our pre or post 1800 play classifier, which also performed well, suggest older plays had more disjoint groups of characters and more distinct plotlines than newer ones. Misclassifications such as Shakespeare’s The Tempest (set on an island where most characters interact with each other), which was misclassified as new, corroborated our hypothesis.

5.3 Movie date classifier

Our movie date classifiers performed poorly. We think this may be due to insufficient data, or no marked difference in interaction patterns between old and new films.

5.4 MPAA and rating classifiers

These classifiers performed poorly, aligning with our expectations because there is a great diversity in the types of movies (and their interaction networks) that are enjoyed by audiences, praised by critics, or given a certain MPAA rating.

5.5 Genre classifiers

Overall, our classifier analysis confirms several common assumptions about genre stereotypes and assumptions. For example, “horror” classifiers performed particularly well, and were often characterized by high average top character relationship strength. This implies that most horror movies have one simple storyline, which is the stereotype.

As another example, romance and comedy proved far too similar to be successfully classified. Upon further reflection, character interaction networks for romances and comedies would be similar; comedies such as Harold and Kumar feature a dynamic duo that interacts much as love interests in a romance would.

5.6 Play author classifiers

Our classifiers achieved rather high AUC’s, and an analysis of the decision trees shows that one of Shakespeare’s defining characteristics is a large spread in the importance of main characters:

6. Conclusion

In this project, we developed a network extraction and classification strategy that sheds light on characteristics that define movies and plays. We automated a literary scholar’s general approach to extracting meaning from movies and plays, leading us to valuable insights about large numbers of works. It is our hope that scriptwriters will be able to use these insights to increase the breadth and diversity of character interactions and counter our generalizations with unique works of entertainment!