MapServer for Swedish Language Technology

July 17, 2013, 15:30 | Centennial Room, Nebraska Union

Introduction

Digital maps can today ensure a convenient and efficient rendering of geographical information in real time. Perhaps the best-known source for providing a search interface to the contents of tens of millions of computers on the internet, together with free of charge digital maps for anyone to use, is the Google Map server. The development of digital maps supported by Google is to a large extent driven by the needs of the industry whose requirements range from weather maps to driving instructions obtained from GPS information. Because of this focus, geographical locations which are found in literary texts — e.g. no longer existing places or older name variants – are not guaranteed to be available in this pool of modern digital maps. Moreover, freely available digital maps are naturally not optimized for all kinds of applications. The maps available on the internet are often copyright-protected. This lack of flexibility and the need to point to geographical locations of places that are found in literary texts are two of the main reasons why our group at Språkbanken ‘the Swedish Language Bank’ [1] have decided to investigate an alternative open-source solution, a platform called MapServer (Kropla 2005). [2]

Språkbanken

The Swedish Language Bank is a research unit which focuses on developing linguistic resources and tools for use by researchers and online visitors from different research fields such as linguistics, language technology, and language learning (Borin et al., 2012a; 2012b). It offers access to a vast amount of written natural language text resources including historical and literary texts. Recently, we have recognized the need of combining place-name recognition with geographical information systems as an alternative source of valuable information about the texts and a way to increase text understanding. The role of geographic visualization in the language learning and usage has been explored in various projects (Lieberman, et al. 2010; Gregory and Hardie 2011; Bibiko 2012).

MapServer at Språkbanken

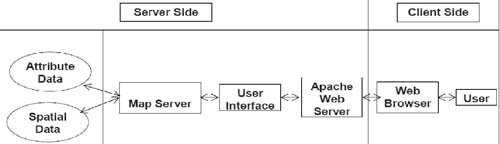

MapServer is an open source Geographic Information System (GIS) development environment for producing maps from geographic data on the Web. [3] Its overall architecture is depicted in figure 1. The user interface provides two different ways to render geographic information: (1) static maps to present a small number of places that appear within the same geographical location and (2) dynamic maps that allow the user to change the amount of data appearing on the map in real time. The geographical dataset consists of both spatial and attribute data and is acquired from Geofabrik. [4] It contains raw data (Open Street Map format) and shape files (Haklay and Weber, 2008). [5]

Figure 1.

The client-server architecture of MapServer.

MapServer accesses an MySQL database to perform coordinate place-name search. This database is automatically maintained by accessing and extracting place-names from the GeoNames database. [6] Because the GeoNames database contains redundant information about place locations, disambiguation is performed. The disambiguation algorithm calculates the Euclidian distance (using the Pythagorean theorem) between places with the same name. If two or more places with the same name occur within three kilometers of each other, only one of these occurrences is added to the database, the one with the most recent modification date. In the case of modification date ties, the place with the highest latitude value is kept.

Visualization of automatically recognized place-names

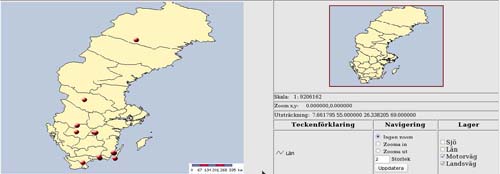

The named entity recognizer (NER) and annotator used for annotating place names from Swedish literature (Borin et al., 2007; Borin and Kokkinakis 2010) automatically extracts names across large collections of texts with very high precision. In the kind of texts we are dealing with, the distribution of place entities across the whole document is quite common. The reader may sometimes lose track of where the story takes place, in particular if the plot of the story ranges over a wide geographical area. For example, in classical Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf’s famous two-part work The wonderful adventures of Nils more than 50 place names are mentioned. A reader interested in learning more about these places will benefit from a visualization of their locations.

With the NER tool it is possible extract the place names mentioned in the text and formulate a query with these names to the MapServer application which will render a dynamic map pointing to the geographical locations corresponding to the names. An example is provided in figure 2.

Figure 2.

A dynamic map of the place names mentioned in The wonderful adventures of Nils.

Summary

The MapServer application used by the Swedish Language Bank provides new opportunities for visualizing geographical information found in its large repository of written texts, in particular literary texts. The application is capable of performing coordinate search on the basis of recognized place names and rendering both static and dynamic maps that display their geographical locations.

References

Notes

2. There are other open-source GIS alternatives, such as GeoServer and PostGIS, that presumably would serve these needs equally well.

4. http://www.geofabrik.de/data/download.html

5. http://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Sv:Map_Features

6. http://download.geonames.org/export/dump/