Linked Jazz 52nd Street: A LOD Crowdsourcing Tool to Reveal Connections among Jazz Artists

July 17, 2013, 13:30 | Short Paper, Embassy Regents E

“There's a bond, a sort of invisible bond between all musicians who play jazz. There is always that bond, it holds them together.” — Ian Patterson, 2009

Introduction

Linked Jazz [1] is a Linked Open Data (LOD) project that aims to create methods and tools that reveal the dense fabric of relationships connecting the community of jazz artists who typically practice in rich and diverse social networks. This project takes advantage of the potential of LOD to connect cultural heritage data in new ways and expand traditional access to archival content by making it visible and discoverable in an open information environment. The Linked Jazz project consists of multiple phases and has progressed in an iterative and experimental process. In the first phase, a LOD dataset representing a social network of connections among jazz artists was created through the automatic extraction of personal names from interview transcripts acquired from digital archives of jazz history. Based on this dataset, a visualization tool was developed that offers static and dynamic views of the social network [2] . While the social network is effective in conveying the vast and rich web of interpersonal associations, its connections remain semantically undefined.

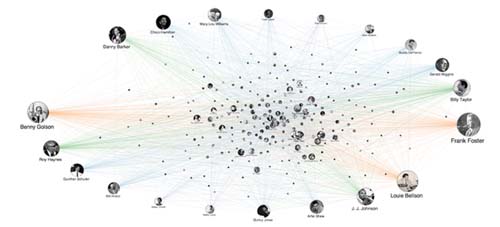

Fig. 1:

Frequency-based network rendering

Enriching the Network

Social network analysis is based on graph theory, in which entities such as individuals are presented as nodes and their relationships are represented by edges between them (Chen & Yang, 2010). While this mathematically-based approach allows for analysis of the network’s structure based on parameters like centrality and clustering, typically, social graphs provide little or no explicit information about the nature of the relationship that connects two entities (Chen & Yang, 2010; Scott, 2011). The need for richer descriptions of social relationships within networks and for researchers to be able to find resources more readily has led to projects that focus on enhancing the visibility and interconnectedness of archival resources. Such projects included the development of Encoded Archival Context-Corporate Bodies, Persons, and Families (EAC-CPF) [3] and Social Networks and Archival Context (SNAC) [4] .

The jazz community is characterized by a high degree of interaction and connectivity. A few studies have examined the interconnectivity among jazz musicians. Heckathorn and Jeffri (2003) studied their affiliation patterns and found that this community is highly egalitarian and cohesive. They employed the respondent-driven sampling method, a technique that requires respondents to know and come in regular contact with one another. Approaching the study of personal connections in this community from a different angle, Schubert (2012) adopts discometrics — the application of bibliometric network techniques to discographic data — to reveal how embedded a particular musician is within the jazz community network.

Human-Generated Approach

The complex and dynamic web of interpersonal connections inherent to jazz music is well documented in books and discographies, yet not easy to discover. While a machine-driven approach combining Natural Language Techniques (NLP) techniques and LOD technology has proven effective in revealing basic connections among personal entities (Pattuelli, Weller and Szablya 2011), this approach fell short when attempting to uncover the nature of artists’ interpersonal ties and provide a more powerful tool for analysis. We can only assume that jazz artists who cite other jazz artists in their interviews have some kind of association with them, but this relationship could be anything from close friendship and collaboration to just knowing the other person exists.

Identifying and representing the varied and nuanced semantics of social relationships pose significant computational challenges. To perform a deeper analysis of the social network, we complemented the machine-driven approach with a human-driven one that employs crowdsourcing techniques to assist with the interpretation of the interpersonal connections. Crowdsourcing has become increasingly popular as a means to harness human intelligence to complete small, but crucial tasks within a large-scale project.

Linked Jazz 52nd Street [5] was developed to harness the knowledge of jazz scholars from academic centers for jazz studies as well as jazz enthusiasts from dedicated online forums to assist with the interpretation of the relationships among jazz artists as documented in archived interviews. This tool is a web-based application that asks contributors to classify the relationship between two jazz artists according to a menu of options. This assessment is facilitated by presenting the contributor with interview excerpts referencing the individuals in question. Results are tallied and converted into RDF statements that feed the project’s LOD dataset. As part of the development of the tool, a list of social relationships was compiled by selecting suitable predicates from LOD vocabularies including the Relationship vocabulary [6] , FOAF [7] , and the Music Ontology [8] . The spectrum of relationships ranges from lower degrees of personal closeness (e.g., knows_of, has_met) to deeper levels of social ties (e.g., collaborated_with, influenced_by, mentor_of). This selection was the result of the analysis and mapping of person-centered RDF vocabularies (Pattuelli 2011). Jazz experts were also tapped to help discern which of these relationships would be of most interest to them and the larger community of potential users of jazz archives.

Linked Jazz 52nd Street Design

Crowdsourcing, a term coined by Jeff Howe (2006) in Wired magazine, was predominantly seen as an online business model, but recently successful projects, including New York Public Library’s What’s on the Menu [9] and University College London’s Transcribe Bentham [10] , have brought attention to crowdsourcing in the domain of cultural heritage as a method of supporting an array of labor-intensive and error-prone tasks including transcribing, classifying, proofreading, tagging, and annotating digital content.

The design of the Linked Jazz 52nd Street application was informed by research on crowdsourcing, as shown in Figure 2. The overall design of the site is geared towards lowering the barrier for participation through a simple and clean layout (Oomen and Aroyo 2011). Several studies have revealed that while extrinsic factors, such as monetary compensation and recognition, are strong motivators to engage in crowdsourcing projects, so are intrinsic factors, such as the opportunity to contribute to the greater good and learn new skills (Brabham 2010). This suggests that acknowledging user contributions through methods such as feedback and ranking of contributors, as well as providing tutorials and interaction with staff, helps to keep users engaged (Causer, Tonra and Wallace 2012; Huberman, Romero and Wu 2009). To this end, we encourage visitors to begin contributing by having a strong call to action message on the homepage asking visitors to click on a musician's photograph. As the contributor processes a transcript, an ego network visualization is built in real time while a progress bar fills indicating their progress (Fig. 2.1). This extrinsic motivator provides visual feedback indicating the immediate results of their contribution and makes their work transparent and accessible (Holley 2010). We also provide the ability for the contributor to put the task in context by expanding the transcript dialog (Fig. 2.2) to read more of the interview. This intrinsic motivator allows the contributor to break out of their current task and read more of the transcript if they find a compelling story or want to learn more about what is being discussed. Holly (2010) highlighted the importance of offering the contributor options of where to focus their work. We facilitate this choice by providing the contributor with the ability to select which individuals they wish to review (Fig. 2.3). Another important aspect is maintaining the provenance of the source information (Oomen and Aroyo, 2011) which we accomplish by including a link to the contributing institution and metadata such as the interviewer’s name (Fig. 2.4). As recommended by Causer, Tonra and Wallace (2012), we provide detailed assistance through a tutorial system and instant popup help tips (Fig. 2.5). We also track and display metrics of the contributors (Fig. 2.6) to acknowledge their work and create a sense of community (Huberman, Romero and Wu, 2009).

Fig. 2:

Linked Jazz 52nd Street design elements

Future plans for Linked Jazz 52nd Street include usability testing to be conducted both with jazz experts and non-experts. Feedback from these tests will inform decisions regarding refinements and further development of the tool before its public release.

Conclusion

Scott (2011) points out that advances in social network analysis should not be simply descriptive work, but rather hold substantive significance. In addition to creating a deep network of the jazz community through the description of relationships at a more meaningful level, Linked Jazz 52nd Street will contribute a new LOD dataset representing jazz artists and their relationships that will be freely available for applications developers. Not only does it give new visibility to jazz archival resources, but it has the potential to promote new streams of research, including a socially-driven approach to the study of jazz history.