Simulation of the Complex System of Cultural Interaction

July 19, 2013, 10:30 | Long Paper, Burnett 115

The crucial issue for space and time in language and cultural study is modeling diffusion, how characteristics spread spatially over time. Diffusion creates the regional and social patterns in language that we all perceive around us at any particular moment in time, and the same is true, though perhaps we notice it less frequently, of other cultural practices such as food ways, architectural styles, clothing styles, folk and cultivated narrative and literary modes, and social roles and relationships. The process of diffusion certainly occurs as a result of cultural interaction — to use language as prime example, massive numbers of people talking (and more recently writing) to each other. The new science of "complex systems" shows that order emerges from such systems by means of self-organization: particular variants come to be more or less frequent among different groups of people or types of discourse (the same nonlinear curve has a different order of variants at every scale of analysis), and variant frequency comes to mark identity of the different regional and social groups. The process of diffusion corresponds to the frequency differences that emerge from our choices of what to say and write, in the buzz and hum of our daily human interactions with each other. However, we cannot observe diffusion directly because it has never been feasible to collect the time series data required to do so. Computer simulation is the only way that we can model diffusion as the adaptive aspect of complex systems in speech and culture (see Gilbert, Miller and Page, Wolfram). This paper describes the construction and implementation of a GIS-aware cellular automaton for use as a multidimensional simulation for speech. Simulations begin with seeding of characteristics across the live cells of a large matrix, say, with linguistic variants seeded along the coast to model original settlement, or with variants seeded across the survey area of the Linguistic Atlas Project (LAP). Throughout thousands of iterations that correspond to the daily interaction of speakers across time, we observe the distributional patterns in the variants as they emerge.

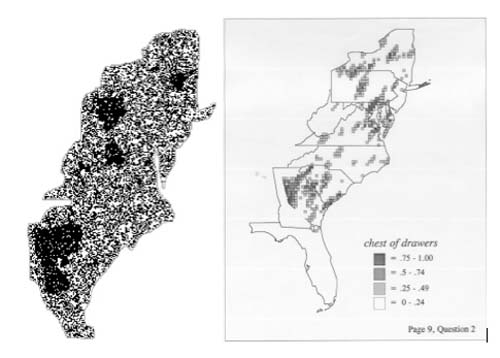

The key feature of this simulation, one not yet attempted to our knowledge, is that we validate it with respect to the emergent "clustered" linguistic distributions known to occur in the LAP, not the actual patterns but instead the sort of pattern that emerges in every elicitation. We know that we have achieved a successful simulation if the result, after hundreds of iterations, is a complex system that shows the clustered distributions we expect in Atlas feature maps (as below; CA at 1000 iterations at left, DE map at right).

In work to date we have demonstrated that such stable clusters do emerge in the simulation as the result of restricted rule sets with a random component included.

When social information is associated with each cell, there is an additional opportunity for weighting the decisions about feature adoption and maintenance. In the LAMSAS matrix of 9000+ cells (after creation of non-active boundaries), 1162 cells have metadata available from the LAMSAS survey. We have interpolated metadata for the empty cells, using the primary social characteristics of urban/rural community type, and informant type (an index showing three levels of education and social integration). These characteristics can be applied to empty cells with respect to the nearest neighbors with metadata in the cellular automaton, with respect also to the overall proportions of the characteristics in the survey as a whole, and also with a small random component. We can execute the interpolation on demand, so that we achieve somewhat different but still valid interpolations for testing the simulation.

Given a matrix with social information available for every cell, we apply social weight to the decision for the presence of the feature of interest in every cell of the matrix, based on the rules assigned for the cellular automaton. The decision to adopt or retain the feature of interest is made by rule according to a certain number of similar neighbors (i.e., adopt the feature of interest if 2, 3, or 4 neighbors have it; retain the feature if 5, 6, 7, or 8 neighbors have it). The proximity of first-order neighbors is the primary characteristic for the decision; in GIS applications it is common to invoke the inverse square law by which a second-order element, twice as far away, has only 25% of the influence of an immediately proximate first-order neighbor. Our method considers social characteristics as second-order phenomena, and assigns a small negative weight of .2 (really, it could be any decimal 0> < .25) to each socially dissimilar neighbor, when a socially-similar neighbor receives the full value of 1 for a first-order relationship. Practical implementation of this policy is to award 1 point to a similar neighbor, and .8 point to a dissimilar neighbor, considering a single social characteristic. When we assign weights to more than one social variable at a time, the cumulative influence of the weight plus the random decision component should not exceed the same .25 as a maximum weight. This means that two social variables might be assigned weights of .1 each, if they were judged to be equally influential, or of, say, .15 and .05 if one social variable was thought to be significantly more important than the other. Overall, social weighting conditions the likelihood for adoption and maintenance of any cultural feature. We will illustrate the effects of including social weighting within a cellular automaton that is essentially proximity driven.

In this way we believe that we are breaking new ground in simulation of cultural interactions as complex systems. The study of speech as a complex system addresses language as an aspect of culture that emerges from human interaction. We believe that successful simulation of speech in cultural interaction as a complex system can suggest how other aspects of the humanities, such as sites or artifacts or styles in archaeology, can diffuse and change across space and time.