Fitting Personal Interpretations with the Semantic Web

July 17, 2013, 08:30 | Long Paper, Burnett 115

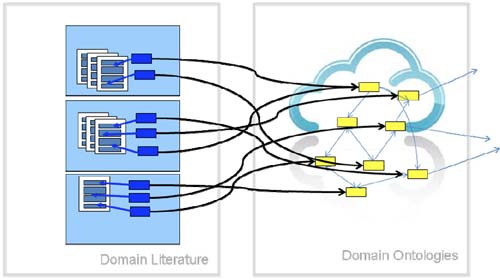

The emergence of formal ontologies into the World Wide Web has had a significant effect on research in certain fields. In parts of the Life Sciences, for example, key research information has been captured in formal domain ontologies, like those mentioned in the Open Biological and Biomedical Ontologies website (OBOFoundary 2012). In parallel with this has been the development of the AO annotation ontology framework (AO 2012) which formalises the act of annotation as a way to connect ontologies such as those in the OBOFoundary to references to them in the scientific literature: an act sometimes referred to as "semantic annotation", and tools such as the SWAN annotation system (SWAN 2008) have emerged to support this. We will call the activity of linking references in a domain literature directly to entities in one or more domain ontologies "direct semantic annotation", and show it in schematic form in figure I. The annotations — shown as heavier lines connecting spots in the literature (to the left) to the ontologies (to the right) could be expressed in the AO annotation ontology, or something similar to it.

Figure 1:

direct semantic annotation

Can direct semantic annotation like this be applied to research in the Humanities? For it to work as it does in the Life Sciences, formal models of humanities materials, built using an ontology framework such as CIDOC-CRM, would need to exist and be already accepted as a useful representation of material of interest to the humanities. Not much of this has happened at present, although perhaps Linked Data initiatives (Heath and Bizer 2011) show some promise in that general direction, and we in DDH are both exploring making data from our projects available in the Semantic Web sense by, for example, setting up SPARQL endpoints, and thinking about the open-data significance of our structured prosopography model (Pasin and Bradley 2012).

Although open, linked data provides a context for exploring direct semantic annotation and even though there is evidence of this being thought useful in the Life Sciences, by itself the mere act of linking a spot in a published online journal to a relevant bit of an online ontology does not represent anything other than rudimentary research activity in either the Life Sciences or in the Humanities. Instead, almost all humanities scholars want to spend their time, not connecting things they read only to an existing, shared, understanding of things, but instead developing their own original interpretation of the materials they study, and they aim to subsequently explore these new concepts and paradigms in articles and books that they write. (see Brockman et al 2001 and in Palmer et al 2009) For traditional humanists, their scholarship does not start out only with predefined formal structures such as those provided through their community's shared concepts, but begins with a set of vague notions and insights that emerge more clearly over time in the scholar's mind as they read, and that only over time becomes clear enough to be described in original published work. For most humanists scholarship (a) is normally personal, (b) is meant to produce original ideas that must first emerge and then mature over time, and (c) even when the ideas are mature enough for publication, represents a structure that is at least "pre-ontological", and perhaps at best only partly compatible with the clarity of ontological modelling.

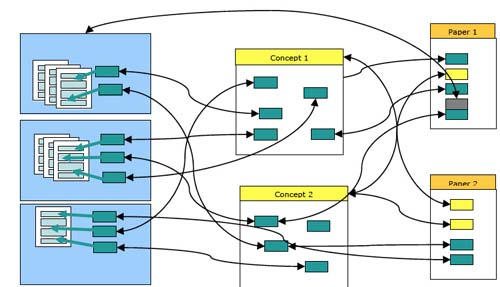

Surprisingly, however, although products of humanities scholarship do not seem currently to match the formalisms of computer ontologies as perhaps some of the Life Sciences do, there is evidence of some degree of inherent structure in the process of creating them. Many researchers, including Brockman and Palmer mentioned earlier, have noted the importance of notetaking and the management of those notes in humanities research. We can see a significantly structured approach around the process of developing new scholarly ideas when we look at traditional strategies for taking and managing notes as described in books like Altick and Fenstermaker's The Art of Literary Research (1992). Altick and Fenstermaker describe paper-based procedures aimed to provide the new researcher with a methodology to organise notes taken while reading into a structure of topics and concepts that will eventually contribute into the writing of articles that represent publishable thinking. There is structure in Altick and Fenstermaker's approach: figure 2 shows this process in schematic form. We see the original notes created during the reading of articles and books on the left, these notes contributing thoughts in the mind of the scholar that eventually allows him to create new concepts in the middle (only 2 "concepts" are shown here, but a real user would have many more), and (towards the right) these new emerging concepts fitting with references to original sources and supporting an argument for new ideas to be presented through the writing of papers. Note the difference from direct semantic tagging in figure I: the annotations do not link directly to preexisting formal ontological entities, but first appear as informal prose notes that may, as the researcher's understanding grows, contribute to a more formal set of ideas and then emerge as entity-like objects in the form of personally developed new concepts, themes, ideas, etc.

Figure II:

a model of the flow of ideas in traditional scholarship

If we wish to explore how traditional personal scholarship could connect to the formal world of RDF and ontology schemes such as the Open Annotations Collaboration (OAC 2011), we need a model that reflects some of these aspects of the act of doing personal scholarship. The models behind the Pliny project (Bradley 2008 and 2012) fit this bill, since Pliny was launched precisely to explore how computing could facilitate exactly this traditional scholarly practice. Pliny tried to be "Englebartian"— referring to Douglas Englebart's H-LAM/T paradigm (Englebart 1962) that successful software integrates with the human way of doing intellectual things so well as to almost disappear, and that this disappearing software can, paradoxically, sometimes allow its users to do entirely new things that they had been previously incapable of doing. Out of this work came two models: the interface which developed a particular view of how users might usefully interact with a note-taking and note management tool to help them develop their own interpretation, and the data model that stored the information. Bradley 2008 describes Pliny's user interface in terms of affordances: 2-dimensional space, containment and hierarchy, naming and labelling and multiple reference of notes material in different contexts, including typing of a reference.

It turns out that Pliny's data model, as well as being designed to represent aspects of traditional scholarship in its three phases, is strongly suggestive of RDF and broader ontological technologies. Like RDF, the structure is a network and the links between the network nodes can be typed in a way similar to a RDF predicate. Pliny from its first release had the ability to export its structure into a Topic Web format, and some preliminary work has been done (see Jackson 2010) to map Pliny data into RDF through the OAC ontology. Further work has been carried out by us to take Jackson's approach further and better map an interpretation as stored in Pliny into an RDF representation.

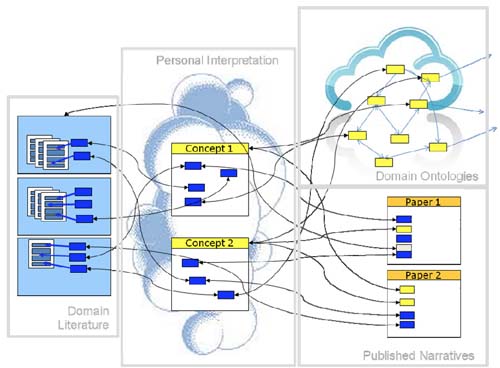

The resulting paradigm is one that, unlike direct semantic annotation (as in figure I), separates the annotation of the domain literature from the highly formal world of shared domain ontologies by injecting a personal interpretative component in-between. One introduces, in ways compatible with semantic web technologies, a personal, more informal, and emerging representation of the scholarship into the picture.

Figure 3:

The place of a structured personal Interpretation

Figure 3 is similar to the direct semantic annotation model shown in figure 1, but adds a structured area, representing aspects of the personal interpretative work of an individual, between a scholar's reading material to the left, and any shared public domain ontologies and linked data to the top right. This interjected personal interpretation "cloud" might well never be as clear-cut as formal ontologies must be, but its presence here recognises and enables the process towards formality that is a central part of interpretation in humanities scholarship. By interposing this somewhat-informal semantic "cloud" between the texts and the formal ontologies of the semantic web, we see a way of thinking about this central personal interpretive work that fits with the larger, more formal, semantic web picture. Although it would seem that the nature of traditional humanities research does not suit the standard direct semantic annotation model currently active in parts of the Life Sciences, we propose here an approach that, over time, encourages the researcher to turn their clouds of personal interpretation into material that might become more and more compatible with computer ontologies and the semantic web.

This presentation will describe work that was first shown in a preliminary fashion in the NeDiMaH Ontology workshop at DH2012 (Bradley and Pasin 2012), but that has continued since then and reaching a significant stage of development.