Documentary Social Networks: Collective Biographies of Women

July 18, 2013, 08:30 | Short Paper, Embassy Regents E

Collective Biographies of Women (CBW) is a collaborative [1] , open-access [2] literary and prosopographical project focusing on published collections of biographies of women [3] . The literary focus of this interdisciplinary project (which also centers in women's history in Britain and the U.S.) concentrates on a popular genre that has received little critical attention. We study the narrative structure of short biographies of diverse women’s lives delineated through interpretive analysis captured in a stand-aside XML mark-up using the BESS schema [4] . Having presented the theoretical and literary aspects in multiple venues [5] , in this short paper we will present emerging prosopographical interpretations of a database of over 1200 volumes, comprising more than 13,000 biographies of more than 8000 women. The women in this corpus come from all walks of life (not simply one occupation or nation, such as the women writers considered by Orlando or Brown's Women Writers Project [6] ), and range from ancient and biblical figures to living contemporaries of the biographers.

In our proposed paper we introduce the phrase, “documentary social network,” as a label for our prosopographical interpretations because we are interested in social networks as discovered in biographical documents [7] . Yet these networks do not always resemble those that can be found in an investigation of Twitter feeds or Facebook “friends” or even of archival materials such as provided by SNAC [8] . The social networks evidenced through our collection of collections are those of documentary grouping and reference. In specialized collections, Christian missionaries in Africa or nurses in World War I may have interacted in historical time and place, but assorted tables of contents commonly link some individuals who never actually shared a "live" event or a relationship or communication. Thus, the relationships are as perceived and presented through printed volumes collecting short versions of biographies.

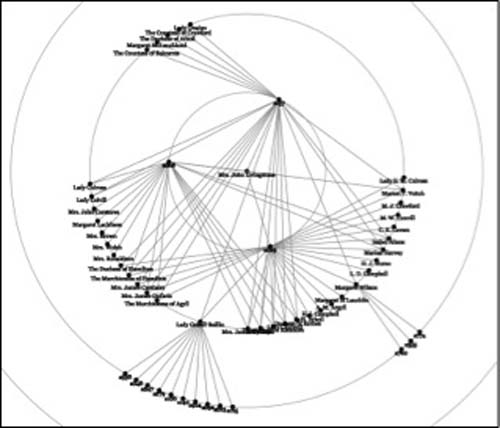

Let us consider one Mrs. John Livingstone. She appears in only three CBW collections and by way of those collections her immediate documentary social network has 37 other women [9] . To visualize this network, Figure 1 is centered on Mrs. Livingstone with the three collections positioned on the innermost circle and the other women of those collections around the second circle. Of her 37 collection “siblings,” nine also appear in these same three collections and nowhere else in CBW, confirming some consensus on the names that represent "Notable Women of the Scottish Reformation," a specific historical episode in one location. Other members of Livingstone's documentary “siblings” range into other collections and in Figure 2 those additional collections are positioned on the third circle. In more eclectic lists, some of the Scottish heroines of religious conflict intersect with a multi-national set of women widely recognized today, including writers such as Harriet Beecher Stowe and heroines of war such as Joan of Arc or the Countess of Montfort. Mrs. John Livingstone’s 267 documentary “cousins” are displayed on the fourth circle in Figure 3 [10] .

CBW's first experiments in digital analysis of narrative structure using the BESS schema have focused on two sample archives that are also productive for this paper's claims about documentary social networks. (Each sample archive is a set of all female collective biographies that include a certain woman, as in Fig. 1.) The two sample archives are "Noble Workers," 20 books that include a biography of Sister Dora, who ran hospitals in the industrial Midlands, and "Women of the World," 14 books that include a biography of Lola Montez, a celebrity in Europe, New York, California, and Australia. These Victorian women never met and never appear in the same book. The mediated interconnections between Sister Dora and Lola Montez appear in Figure 4. Only two women, Marie Antoinette (presented as a victimized queen) and Jenny Lind (the celebrated, virtuous singer), appear with Sister Dora in one collection and with Lola Montez in another (i.e., within one degree of separation of both Dora and Lola). The multiple versions of the lives of 141 women who "network" with Sister Dora in Noble Workers collections, compared to the versions of the 133 persons linked to Lola Montez in Women of the World books, will demonstrate the utility of our approach to analyze historical social networks and nonfiction narratives of many kinds. In spite of the vast differences between two Victorian women — one a saintly nurse, the other a notorious courtesan and performer — we discover patterns among their associates and their proximity in the CBW documentary social network.

These prosopographical networks reveal unexpected affiliations among different types of women, life stories, and collections; with the CBW tools for searching and visualization, we are now able to calibrate not only frequencies and proximities of persons and publications over time, but gradations of rhetorical assessment of women's roles and deeds, according to the perspectives of these publications [11] . Such multivalent interconnections not only cross categories but also historical periods in significant ways. An example is the connection between Sister Dora and Anne Boleyn, shown in Figure 5. This diagram reveals that the middle-class, now-forgotten Englishwoman, Sister Dora, appears with her contemporary queen, Victoria (in seven books), and in two collections with the martyred queen, Jane Grey (one of the latter, a186 [12] , is a book that Victoria also shares), but not with Henry VIII's second wife [13] . At sufficient scale, and integrated with other elements in our analysis, data on frequency or "distance" in networks can lead to productive interpretations. Anne Boleyn, unlike good Lady Jane in ambition and sexual notoriety , but like her in being executed because of the politics of English monarchy, features in 24 collections, including 11 dedicated to English queens and three focused on the English Reformation; the latter three collections include Lady Jane Grey but not one of the obscure Scotswomen of Mrs. Livingstone's ilk. To put it simply, Boleyn serves English and Protestant history, but not the promotion of feminine virtue, heroism, or social service.

More complex documentary interrelationships can be seen in Figure 6, associating the Gothic novelist Ann Radcliffe (dead before Sister Dora was born) with Sister Dora through a range of widely respected eighteenth-and nineteenth-century women writers; these lists also commend Jeanne d'Albret, the French queen regnant who championed the Calvinist Huguenots, as well as Lady Russell, Mme. Roland, and Lady Jane Grey, represented as good, highly educated women who played indelible parts in the history of their countries in revolutionary times.

Our proposed paper will present the methods and implications of prosopographical analyses afforded by the CBW documentary social network. Our demonstration of documentary social networks has implications for any "personography," as well as for historical studies of women and studies of biographical narrative. We argue, in this paper, that digital exploration of the persons, narratives, collections, and documentary social networks in the CBW genre opens a prolific field of ramifying versions of female biography impossible to decipher through an approach to individuals or single full-length biography, and invisible through the customary lenses of historiography, time and period, place and nationality.

Figure 1:

Mrs. John Livingstone and her 37 documentary siblings.

Figure 2:

The 16 collections containing Mrs. John Livingstone and her documentary siblings.

Figure 3:

Mrs. John Livingstone and her 267 documentary cousins.

Figure 4:

Connections between Sister Dora and Lola Montez.

Figure 5:

Connections between Sister Dora and Anne Boleyn.

Figure 6:

Connections between Sister Dora and Ann Radcliffe.