Open Notebook Humanities: Promise and Problems

July 19, 2013, 13:30 | Long Paper, Burnett 115

“When found, make a note of” (Dickens 1848, 149). In 1849, William Thoms took this rule as the motto of his new journal Notes and Queries, observing that following this rule for any length of time will result in “a good deal of matter in various forms, shapes and sizes . . . [in] countless boxes and drawers, and pigeon-holes of such things, which want looking over, and would well repay the trouble” (Thoms 1849, 1–2). Thoms could have been describing the offices of a contemporary documentary editing project, except that these days the “pigeon-holes” include shared hard drives. Good documentary editors follow this rule scrupulously, and as their projects stretch on into multiple decades, they amass a rich storehouse of notes, which would indeed repay the trouble of those who would look over them. Yet few have this opportunity, as only a small fraction of the content of these notes are ever made available.

Our aim in the Editors’ Notes project (http://editorsnotes.org/) is much the same as that of Thoms in 1849: to provide a “medium by which much valuable information may become a sort of common property among those who can appreciate and use it” (Thoms 1849, 2). Much recent work in the digital humanities has focused on exploring ways to use networked computing to change scholarly practice. Tools like Zotero encourage open sharing of bibliographic data (Cohen 2008). Sharing of scholarly annotations has also been widely explored, and the Open Annotation Collaboration is working on developing standards and tools for making annotations interoperable across multiple tools (Hunter et al. 2010). Various projects have experimented with widening participation in humanist scholarship through “crowdsourcing” (Causer, Tonra, and Wallace 2012). Other projects have sought to banish the stereotype of the “lone scholar” through experiments in collaborative authorship of edited volumes (Dougherty and Nawrotzki 2012). And considerable effort has been made to increase access to the products of humanist scholarship through the creation of open access journals, monographs, and scholarly editions, most of these building upon a well-established humanities practice of digital editing and publishing.

These various projects address many aspects of the humanities research process. But notes have been curiously overlooked. Reference management tools like Zotero do enable shared note taking on individual documents, but this functionality is secondary to the management and sharing of bibliographic data. Other projects primarily focus either on managing research “inputs” such as annotations and transcriptions of source documents, or on “outputs”—finished scholarly products—whether these are books, databases, or virtual environments. With Editors’ Notes we are addressing the space in-between: the writing, organization, and linking of working notes, which are relevant to source documents but not necessarily tied to any specific document, and which may or may not become a formal finished product.

While not yet widely explored in the humanities, this space is one that has recently received much attention in the sciences. Both the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation have instituted data sharing policies that encourage the researchers they fund to make

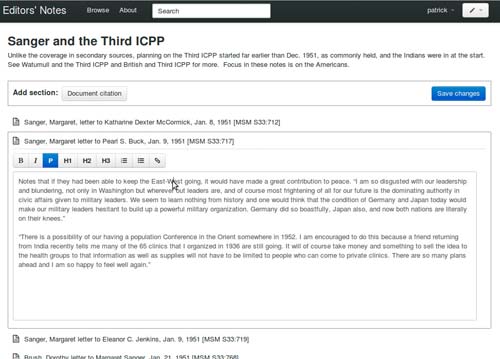

Figure 1.

Editing one section of a note on "Sanger and the Third ICPP."

available to other researchers the final research data underpinning their published work. “Open notebook science” presents a more radical vision in which not just the final research data, but all data generated during every stage of the research process is captured and made publicly available, either in “real time” or at the conclusion of a project. Advocates of this radically transparent approach to scientific practice expect it to result in more verifiable and reproducible research results, more efficient management and re-use of data on both the local and global levels, and new forms of algorithmic and “crowdsourced” research (Velden and Lagoze 2009).

The case for open notebook science rests upon the recognition that data from failed or incomplete experiments are potentially as important as those from successful ones. The problem is that current models of scientific publishing provide few incentives to publish such data, nor are there places to put it. Historians face similar problems, especially those engaged in long-running projects like documentary editions that may involve dozens of researchers working over decades. It is typical for a researcher to spend hours upon hours researching a topic only to find that she has duplicated work done years earlier and stowed away in a file cabinet or on a floppy disk.

William Thoms recognized back in 1849 that a major benefit of sharing working notes would be to induce researchers to “look over their own collections” and, by allowing others access, improve their own chances of finding past work (Thoms 1849, 2). In other words, a researcher need not be motivated by scholarly altruism to share her work. Yet Thoms believed that were sharing of notes to become cheap and frequent, then researchers would not hesitate to give help, not only to others engaged in similar lines of research, but also to “those who are going different ways, and only meet at the crossings” (Thoms 1849, 2). As this research commons grew, so would the opportunities for such crossings, and the net result would be more efficient research at the global level as well as the local.

Thoms’ vision is echoed in efforts by the scientific community to create publishing models that enable both finer-grained publication units (Mons and Velterop 2009; Groth, Gibson, and Velterop 2010; Mons et al. 2011) and new attribution practices (Nature Genetics 2007; Nature Genetics 2008; Giardine et al. 2011). These efforts recognize that citing published work helps drive scientific publication. They aim to expand the universe of citable work beyond the canonical research paper to units as small as individual statements. In doing so they hope to make visible the great iceberg of scientific work of which published papers are only the tip.

Scholarly footnotes such as those produced by documentary editors can be viewed as a form of nanopublication. One of the goals of the Editors’ Notes project is to give the status of individual publications to footnotes and the working notes that led to those footnotes. These notes can be complemented by machine-readable “factoids” (Bradley and Short 2005) about people, places, organizations, and events, drawn from open-access linked datasets (Heath and Bizer 2011). Scholars can assess and improve the quality of these factoids, connecting assertions to bibliographic descriptions of evidential resources and publishing “gold standard” datasets that meet their high standards (Shaw and Buckland 2011). The scholars’ notes provide context for the otherwise bare factoids, documenting why and to what extent they have chosen to accept them and the conclusions they have thus drawn.

Mons and Velterop (2009) make a distinction between “curated” and “observational” statements in scientific discourse. “Curated” statements take the form of records in trusted scientific databases. For example, a database recording known protein interactions may contain statements about these interactions along with metadata describing their context, conditions and provenance. In contrast, “observational” statements are factual statements such as “malaria is transmitted by mosquitos” that have not been formally recorded in any database but nevertheless are commonly asserted. A goal of nanopublication is to build knowledge bases that transform observational statements into curated ones.

History and the humanities mostly lack the databases of curated statements that exists in the sciences. The closest equivalents might be prosopographical or genealogical databases (Bradley and Short 2005; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 2012) or digital historical gazetteers (Elliott and Gillies 2011). These are exceptions that prove the rule, however, and the vast majority of factual statements in history and the humanities remain at the observational level.

To facilitate the shift from closed, personal or project-specific notes to openly shared notes, we’ve had to address a number of challenges. Editorial projects take varying approaches to structuring their research workflow, dividing labor among editors and student assistants, and standardizing on naming and citation practices. We have attempted to accommodate these varying work practices while creating opportunities for standardization across projects where it is desired. Our efforts to accommodate existing practices align with the broader objective of not disrupting ongoing research by integrating with research tools already in use. For example, Editors’ Notes integrates with the Zotero bibliographic data management platform, allowing researchers to access their existing bibliographic databases (Shaw, Buckland, and Golden 2012).

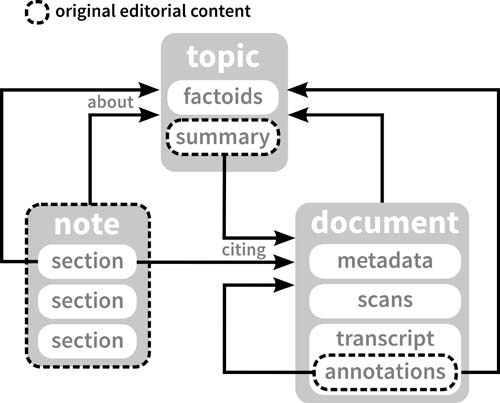

A major challenge has been developing a data model for notes that is flexible enough to accommodate a variety of working styles (Figure 2). We have tried to support fine-grained addressing and indexing of notes, allowing researchers to search for and link to notes taken on a single source document as it relates to one narrow topic. At the same time, we have sought to develop ways that researchers can work with aggregations of these small “atoms” in ways that feel natural to them. For example, notes taken while researching “the status of birth control in India in the 1930s” might reference dozens of documents encompass several more specific topics such as the Indian birth control activist Dhanvanti Handoo Rama Rau, birth control clinics, and the Bombay Municipal Corporation. Researchers can work with these notes in the context of the broader research task, or they can pull together all the notes about Rama Rau, whether or not these were taken in the course of researching “the status of birth control in India in the 1930s.”

Figure 2.

Part of the Editors' Notes data model. Notes, sections of notes, and topic summaries may cite document. Notes, sections of notes, documents, and document annotations are linked to the topics to which they relate.

Another ongoing challenge has been the question of how to bridge the gap between note-taking practices in scholarly research projects and those of curators of special collections and archives. The Joseph A. Labadie special collection of radical history at the University of Michigan helped us explore this question by providing thousands of notes created by Agnes Inglis, the first curator of the collection. The subject matter of these notes overlapped with that of the editorial projects involved, but these “curator’s notes” turned out to be useful less for their content per se, than for the metadata infrastructure (network of relationships among names and other topics) they produced. This realization helped catalyze our ongoing experimentation with incorporating linked data from libraries and archives.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for funding “Editorial Practices and the Web” (http://ecai.org/mellon2010) and for the cooperation and feedback of our colleagues at the Emma Goldman Papers, the Margaret Sanger Papers, the Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Papers, and the Joseph A. Labadie Collection.