Live Coding Music: Self-Expression through Innovation

July 17, 2013, 15:30 | Centennial Room, Nebraska Union

Musical live coding is a relatively new discipline that explores the manipulation of audio and music through altering a program in real-time, frequently while projecting the music-generating code in front of an audience (TOPLAP, 2012). Live coding falls under both the realm of computer music and computer science in a blend of programming and artistic output. Pioneering live coders often write their own languages, adapt existing environments, and create unique interfaces and control mechanisms for their systems (McLean and Wiggins, 2010). The frequency of this personalization gives rise to two important questions: in spite of the presence of existing, similar environments, why are live coders creating their own systems and what types of changes are they making to the musical and programming functionality of their environments?

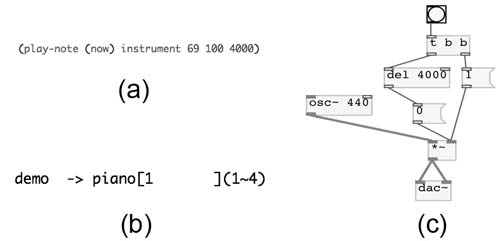

The questions are addressed by a comparative study of a wide range of live coding environments, the literature on live coding, and by interviews with active live coders. The types of implementations the environments use for musical expression and the rationale provided by their creators illustrate the many routes that live coders are taking to explore musical creativity and programming intricacies (for discussion of this creativity, see Collins, 2011; Magnusson, 2011; and McLean and Wiggins, 2010). From community supported languages such as SuperCollider (McCartney, 2002, 2012) and MAX/MSP (Puckette, 2002) to individually crafted, younger languages like Sorensen’s Impromptu (2013), Fluxus (Griffiths and Papp, 2012) and Tidal (McLean, 2011), the study shows that all live coding environments must find solutions to the issues of musical representation, time passage, audio creation, and programming paradigm, and it is in these differences and similarities between environments that individual strategies of the live coders become apparent. Figure 1 shows a single note expressed in multiple environments, illustrating the differences between them.

Figure 1:

A sustained note at 440 Hz in three environments used for live coding audio:(a) Impromptu, (b) ixi lang, and (c) Pure Data (see Sorensen, 2013; Bausola et al., 2013; and Puckette 2013, respectively).

The dedication to individuality in live coding has led to a wide range of methods, goals, and musicality that, as of yet, has no formal theory to describe or categorize the products and notations of live coding (McLean and Wiggins, 2010). Therefore, this study categorizes methods used by live coders in a prototypical music theory. The study concludes that live coders create and modify their own environments because musical improvisation and on-the-fly composition demand a certain familiarity with a programming environment that is not easily obtained by adopting an existing system (see also Brown, 2006). Additionally, the study proposes that live coders prefer their own environments to others’ because live coders are as interested in the processes behind making the music as they are in the music itself(see also Brown, 2006; Brown and Sorensen, 2009; and Aaron et al., 2011). By adapting their programming environments, live coders explore the boundaries of their processes and the impact that constraints, interfaces, and techniques have upon the musical output.

The presentation includes descriptions and examples of code illustrating the different treatments that live coders use when approaching musical or programming requirements. These include the passage of time, ensemble coordination, and types of code interfaces. A laptop will be provided to offer a hands-on interactive comparison of several live coding languages, and an ongoing, paper-based live coding game will encourage participation throughout the course of the conference (Nilson, 1975).