The DARIAH Approach to Interdisciplinary Interoperability

July 17, 2013, 10:30 | Short Paper, Embassy Regents F

Introduction

In this paper we present the preliminary results of the work that is being carried out in the framework of the DARIAH-DE [1] project on the topic of interdisciplinary interoperability. DARIAH-DE is the German branch of the EU-funded Digital Research Infrastructure for the Arts and Humanities (DARIAH) project with 17 institutions belonging to a wide range of disciplines as project partners. This fortunate circumstance compelled us to tackle the problem of how to achieve greater interoperability between the digital collections of institutions coming from different disciplines.

We first present our pragmatic approach to interoperability and then discuss some use cases that were developed to complement a set of recommendations on interdisciplinary interoperability. These recommendations are meant, on the one hand, to help Humanities institutions to integrate their collections into the DARIAH data federation and, on the other hand, to let them benefit fully of the services provided by the infrastructure.

The importance of interoperability when building a research infrastructure becomes evident as soon as one considers, for example, even a basic search mechanism over several collections, also known as federated search. Building such a federated search requires institutions to expose, at least, an end-point that can be harvested using a given protocol (Aschenbrenner, et al. 2010). The Collection Interoperability group in Bamboo — an analogous infrastructure project in the United States — was faced with the same problem of making collections interoperable and decided for developing adapters to make collections compliant with the OASIS Content Management Interoperability Services (CMIS) standard. Let us see now what has been DARIAH's approach to interoperability.

Methodology

If interoperability is difficult, true interoperability across disciplines is perhaps even more so as — particularly when talking about semantic interoperability — the narrower is the application domain the higher are the chances of achieving some results. This is the case, for example, when using ontologies for this purpose as shown by (Marshall and Shipman 2003).

Therefore, given the number of domains and disciplines that DARIAH is trying to cater for, the solution of mapping the meaning of content in different collections onto the same ontology or conceptual model appeared soon to be not a viable one. As Bauman makes clear while discussing the topic of interoperability in relation to the goal and mission of TEI (Bauman 2011), the drawback of adhering to standards for the sake of interoperability is the consequent loss in terms of expressiveness.

Instead,DARIAH position on this respect is of allowing for crosswalks between different schemas: a sort of “crosswalk on demand”. Infrastructure users will be able to use the Schema Registry — a tool which is being developed in DARIAH-DE — to create crosswalks between different metadata schemas so that they are made interoperable.

Our main goal was to devise a set of guidelines that is realistically applicable by partner institutions as part of their policies. Therefore, the first preliminary step was to gather and analyze information about the digital collections of the partners with regard to interoperability. We identified the following key aspects to guide our analysis:

- 1 Identifiers: two aspects of identifiers were considered: on the hand, their persistence over time, which is a crucial aspect for any infrastructure project, and on the other hand the use of common, shared identifiers(e.g. controlled vocabulary URIs)to express references to the same “things”, that is one of the core ideas of Linked Data.

- 2 APIs and Protocols: APIs and protocols are essential as they allow for workflows of data access and exchange not necessarily dependent on human agents. This idea is implied in the notion of “blind interchange” discussed by Bauman with the only difference being that, in our own vision, as little human intervention as possible should be required.

- 3 Standards: using the same standard is in some, if not many cases, not enough to achieve real semantic, not only syntactic, interoperability. Therefore we discuss further aspects of standards in relation to interoperability such as multiple serializations of the same scheme, and the problem of adoption and adaption of schemes to different contexts.

- 4 Licences: licences, and specifically their machine-readability, play — perhaps not surprisingly — a crucial role within an interoperability scenario: not only should a licence be attached to any collection as soon as it is published online, but such licence should also be readable and understandable, for example, to an automated agent harvesting that collection.

Use Cases

The main aim of the use cases was to show how basic, minimal standards, such as the OAI-PMH protocol, can be exploited together with already existing and re-usable tools in order to devise more advanced interoperability scenarios. The requirements of such use cases were that they could be implemented in a limited amount of time, without requiring much programming effort and using openly available tools and data coming from partner institutions.

Static OAI-PMH

The first use case focussed on tools that can be used to create an OAI-PMH end-point for collections without having to set up an own repository as this could be a problem particularly for small institutions or poorly funded disciplines. Since OAI-PMH will be part of the recommendations as the minimal protocol for accessing collections, we wanted to explore ways so to overcome the barriers to adopting it. We used as data collection a sample of Kalonymos [2] , a journal published by the Steinheim-Institut (STI), as it does not provide yet such an interface. The Dublin Core metadata for the articles in Kalonymos, stored in a static file, were then served by an OAI-PMH end-point created out of such static file by using the OAI-PMH Static Repository Gateway [3] , a piece of software written in C and openly available.

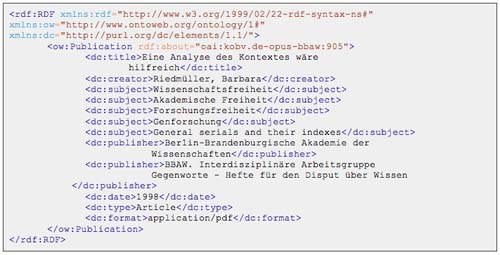

Fig. 1

Sample output of RDFizer.

OAI to LOD

The OAI-PMH protocol is central also in the second use case, which seeks to show how the metadata served by an OAI-PMH end-point can be harvested and programmatically transformed into an RDF representation, more suitable for example in a Linked Data scenario.

The data we used come from a document repository of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Science [4] containing Open Access publications by the academy members. We were able to transform into RDF the Dublin Core metadata served via the OAI-PMH interface of the repository by running the open source OAI-PMH RDFizer [5] .

The so obtained output, see fig. 1, could be enriched by adding links for example to the subject headings contained in the Gemeinsame Normdatei (GND) catalogue of the German National Library (DNB) [6] that are already available as RDF. However possible, this enrichment was not implemented for this use case as it required some extra work to overcome the lack of a lookup API or SPARQL end-point on the DNB side.

Marc21 to SKOS/RDF

The third use case consisted in transforming the thesaurus of the German Archeological Institute, currently encoded in Marc21XML and accessible via an OAI-PMH end-point, into an RDF representation of the same data encoded in SKOS — the W3C standard to publish Knowledge Organization Systems in the Semantic Web [7] .

Such transformation was made possible by the Stellar Console, an open source tool developed by Ceri Binding and Doug Tudhope(Keith et al. 2012) in the framework of the AHRC-funded project “Semantic Technologies Enhancing Links and Linked Data for Archaeological Resources”(STELLAR) [8] . The 80,00 Marc21 records of the thesaurus, after being harvested via the OAI-PMH interface, were transformed into an intermediate CSV file, which is in turn fed into the Stellar Console in order to produce a SKOS/RDF output consisting of slightly less than 1 million triples (Romanello 2012).

TEI to CIDOC-CRM

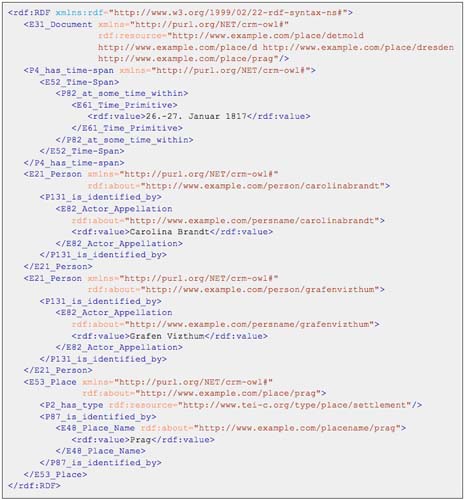

The last use case is another example of extracting more deeply structured semantic information from legacy data, in this case some letters, encoded in TEI, that are part of the project Carl Maria von Weber — Collected Works (WeGA) [9] .

We ran the TEI documents through an XSLT transformation written by Sebastian Rahtz [10] and included as part of OxGarage [11] , an online toolkit for the conversion of TEI-compliant documents into other formats. What this transformation does is to look for elements of specific types and to transform them into equivalent statements expressed by means of the CIDOC-CRM ontology and encoded in RDF/XML.

Straight out of the box, the tool created the corresponding semantic statements for the elements <date>, <persName> and <placeName>. As we observed also for use case 3, it is technically possible to enrich the RDF output by adding the URIs of the person or place that is being referred to in the document. This could be realized by leveraging the links to authority lists that are often included directly into the TEI elements, but the required effort goes beyond the scope of our current work.

Fig. 2

Sample output of OxGarage

Conclusions

We hope that the use cases above have shown how the use of open standards and protocols combined with open source, thus adaptable and reusable, tools can allow us to achieve some greater interoperability in a cost- and time-effective way.

References

Notes

2. http://sourceforge.net/projects/srepod/

4. http://edoc.bbaw.de/oai2/oai2.php

5. http://simile.mit.edu/repository/RDFizers/oai2rdf/README.txt

6. http://www.dnb.de/EN/Standardisierung/Normdaten/GND/gnd_node

7. http://www.w3.org/TR/skos-reference/

8. http://hypermedia.research.glam.ac.uk/resources/STELLAR-applications/

9. http://www.weber-gesamtausgabe.de/en/

10. http://www.zde.uni-wuerzburg.de/tei_mm_2011/abstracts/abstracts_papers#c249172

11. http://www.tei-c.org/oxgarage/