Citation studies in the humanities

July 17, 2013, 10:30 | Long Paper, Embassy Regents C

Abstract

This paper examines prospects and limitations of citation studies in the humanities. We begin by presenting an overview of bibliometric analysis, noting several barriers to applying this method in the humanities. Following that, we present a novel online tool for extracting and classifying citations in the humanities. This tool uses both document layout recognition and natural language processing techniques to classify citations in three ways: frequency, location-in-document, and polarity.

Background

Since the 1970s, bibliometrics has been an important method of analysis in studies of scholarly communication and the structure of academic networks that emerge from it. Bibliometricians typically focus on formal citation behavior in the printed scholarly record, occasionally supplemented with additional information. In the humanities, bibliometrics may also hold promise for tracing intellectual influence, especially when supplemented with social data (Sula 2012).

Bibliometric studies have typically focused on scientific and technical corpora, despite the fact that much intellectual history is located in the humanities (Hérubel and Buchanan 1994; Lamont 2000). This lack of attention may be explained by several factors. First, citation data in the humanities has been less available than in the sciences (Linmans, 2010), especially for monographs (Hammarfelt, 2011), which still form the backbone of humanities scholarship (Larivière, et. al. 2006), and for older sources, which humanists cite with greater frequency (Heinzkill 1980). As humanities citation data becomes more prevalent, digital humanists are likely to engage more fully with bibliometrics, and Smith’s recent article on citation in classical studies is a notable example of this crossover (2009).

A second and more persistent barrier to applying bibliometrics to the humanities involves special features of humanities discourse. Studies show that humanists do engage in patterns of cocitation (Leydesdorff, Hammarfelt, and Salah 2011), but they credit each other less frequently than scientists credit each other (Heinzkill 1980; Swales 1990; Hellqvist 2010), and they rarely publish multi-authored articles (Price 1966; Pao 1981, 1982; Sievert and Sievert 1989; Wiberly 1989). Linmans (2010), for example, reports that journal publications in the humanities between 1980 and 2007 averaged a flat 1.06 authors per article. More importantly, the mere fact that one humanist references another says little about the type or significance of the relationship between the two. Several studies have shown that humanists are more likely than scientists to use integral references, which tend to associate their own views with those they references (Swales 1990; Hyland 1999; Harwood 2008), as well as negative references, which object to other authors’ claims (Meadows 1974; Brooks 1985; Cano 1989). Even studies that disambiguate acknowledgments into different types, such as conceptual, editorial, financial, instrumental/technical, etc. (Cronin, Shaw, and Le Barre 2003), fail to capture qualitative elements of author ties, such as agreement, disagreement, intellectual indebtedness, and so on. These different reference contexts cannot be ignored, since intellectual disputes are the bread and butter of humanists.

Given how these nuances affect intellectual history and scholarly influence, reference contexts must be given greater attention in bibliometric studies of the humanities. Several classification schemes for references have been offered (see Table 1). Though there is some convergence in terms of positive, negative, and neutral/mixed contexts, few schemes are based on empirical research and even fewer lend themselves to practical application; many require subject domain expertise and human classification—a task that is far beyond current resources. In addition, several schemes also attempt to use citation context to sort references according to their importance within a work their prominence within the field as a whole (e.g., “historical,” “classic,” “homage”). In our view, this unnecessarily complicates classification schema. We argue that overall prominence is best estimated by extracontextual measures (e.g., pure or normalized citation counts), and we follow Maričić, et. al. (1998) in taking the frequency of each citation and its location-in-document to be important clues to a citation’s role. For example, a reference cited throughout a work is quite different from one cited frequently at the beginning of that work, which usually helps to establish field background.

| Positive | Neutral/Mixed | Negative | |

| Garfield (1965) | homage -pioneers -peers methodology substantiating claims authenticating data/facts |

background alerting forthcoming work original publications -discussion -eponymic concepts priority claims |

correction -self -other criticism negative homage -ideas |

| Chubin & Moitra (1975) |

affirmative -essential --basic (1) --subsidiary (2) |

-supplementary --add info (3) --perfunctory (4) |

negational -partial (5) -total (6) |

| Moravcsik & Murugesan (1975) |

evolutionary confirmative |

conceptual–operational organic–perfunctory |

negational negational |

| Frost (1979) | (primary texts) -support opinion/fact --about specific author(s)/work(s) discussed --outside of central topic (secondary texts) -approval --support opinion/fact --take a step further --acknowledge indebtedness |

(secondary texts) -independent --meaning of term --acknowledgement --state of the field (neither primary nor secondary text) -further reading -bibliographic information about an edition |

(secondary texts) -disapproval --disagree with fact/opinion --express mixed opinion |

| Smith (1981) | organic-positive | perfunctory-positive perfunctory-negative |

organic-negative |

| Small (1982) | applied (used) supported by citing work (substantive) |

noted only (perfunctory) reviewed (compared) |

refuted (negative) |

| Peritz (1983) | setting the stage background methodological -design -method of analysis comparative argumental/speculative/hypothetical documentary historical casual |

||

| Cullars (1990) | positive | mixed neutral -springboard for discussion -establish background -support interpretation -supplementary readings |

negative |

| Cullars (1992) | positive | value-free -historical background -cultural background -recommended readings -biographical data -support interpretation -scientific background |

negative |

| Shadish, et. al. (1995) |

supportive | personal creative classical social |

negative |

| Camacho-Miñal & Múñez-Nickel (2009) |

evolutionary confirmative |

conceptual operational organic perfunctory other |

negational juxtapositional (?) |

Method

Based on this background literature, we propose an online citation extraction tool that examines PDF documents for citations and reports the frequency of a given reference as well as its location-in-document (relative to the length of the document). In addition, we propose a sentiment classifier that assigns a “polarity” value to each citation on a positive–negative scale (e.g., “I associate with…” and “I disassociate with…”). Sentiment classifiers attempt to determine whether particular sentences or documents express positive or negative opinions about a given topic (Jurafsky and Martin, 2008). This classification is found in nearly all of the other systems surveyed in Table 1, and we hypothesize that it is especially important in the humanities, since it predicts patterns of agreement and disagreement among scholars.

The sample set for this study is 159 articles from four humanities journals (see Table 2). Our choice of journals follows Knievel and Kellsey’s (2005) use of eight humanities journals from 2002 and allows for comparison with their citation frequency results. These journals also reflect a range of citation layout formats, which helps to ensure the usefulness of the tool in other contexts.

| Journal | Year | Discipline | Format | Number of articles |

| Art Bulletin | 2009 [1] | art history | endnote | 37 |

| Journal of Philosophy | 2011 | philosophy | footnote | 30 |

| Language | 2011 | linguistics | inline, bibliography | 18 |

| PMLA | 2011 | language and literature | endnote, bibliography | 74 |

The tool uses document layout patterns to extract each citation and the context of its occurrence—usually a sentence or two. Our website presents this text to users and allows them to select n-gram phrases from context that demonstrate positive or negative polarity. These phrases are compiled into a naive Bayes classifier training set which can predict polarity in novel contexts. The classifier reports polarity scores as probability assignments on two separate scales (positive and negative) each ranging from 0 to 1. Thus, a perfectly positive context would have a score of 1 on the positive scale and 0 on the negative scale. These scores may be combined into a single scale with -1 being purely negative, 0 being neutral, and 1 being purely positive.

Results

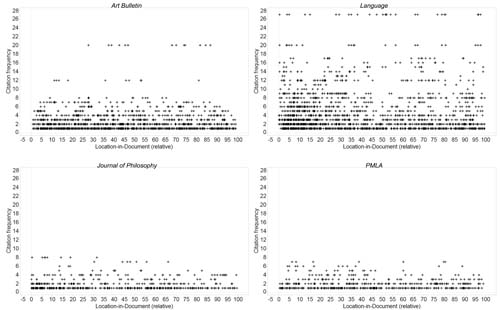

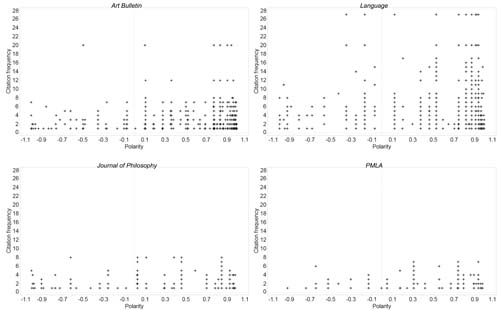

Aggregate results for frequency, location-in-document, and polarity in the sample set are reported in Table 3. Raw figures are visualized in three scatterplots comparing frequency and location-in-document (Fig. 1), location-in-document and polarity (Fig. 2), and frequency and polarity (Fig. 3).

| Journal | Citations detected |

Frequency per citation (avg. ± stdev) |

Relative location-in- document (avg. ± stdev) |

Polarity (avg. ± stdev) |

| Art Bulletin | 1681 | 2.38 ± 2.36 | 43.81% ± 27.69 | 0.68 ± 0.37 |

| Journal of Philosophy | 713 | 1.78 ± 1.38 | 37.74% ± 29.09 | 0.52 ± 0.49 |

| Language | 2374 | 4.24 ± 4.58 | 38.77% ± 30.44 | 0.75 ± 0.31 |

| PMLA [2] | 604 | 1.83 ± 1.28 | 44.95% ± 27.96 | 0.57 ± 0.33 |

Figure 1.

Citation frequency and location-in-document

Figure 2.

Citation frequency and polarity

Figure 3.

Citation location-in-document and polarity

Disciplinary differences in frequency and polarity are especially evident, as is clustering near the beginning of articles.

Future directions

Though automated results were checked informally in the context of manual polarity classification, each article should be manually inspected to determine the reliability of the extraction tool. Patterns of error here may help to improve the citation extraction techniques. In addition, further training of the sentiment classifier would help to clarify the resolution of polarity scores, especially at the positive end. In particular, we are interested in examining the power of crowdsourced classifications for improving the results of classifier and for providing new document layouts that will increase the flexibility of the tool.

References

Notes

1. The 2009 issues of Art Bulletin were used because of their high OCR quality as compared to available 2011 editions.

2. Citation detection in PLMA exhibited several weaknesses at the time these proceedings were due. We believe these errors are due to OCR abnormalities, particularly errant spaces within words, as well as a varied mixture of parenthetical and in-text citation styles by authors. We continue work on refining the tool for these documents.