WordSeer: An Integrated Environment for Literary Text Analysis

July 17, 2013, 15:30 | Centennial Room, Nebraska Union

Summary

I will present WordSeer, an environment for literary text analysis. Literature study is a form of sensemaking: a cycle of reading, interpretation, exploration, and understanding. While there is abundant technological support for reading text in new ways through visualizations and algorithms, the other parts of the cycle — exploration and understanding — have been relatively neglected. WordSeer integrates tools for algorithmic text processing with interaction techniques that support the interpretive, exploratory and note-taking aspects of scholarship. Its design has been shaped by individual case studies with literature scholars as well as a semester-long field trial with a class of undergraduate Shakespeare students.

Proposal

To date, text analysis systems for humanities scholars have focused on aiding interpretation (Clement 2008; Fekete, et al. 2000; J. Guldi, et al. 2012; X. Llorà, et al. 2008; C. Plaisant, et al. 2006; G. Rockwell, et al. 2010; R. Vuillemot, et al. 2009). First, they apply some form of natural language processing to extract aggregate statistics about word usage, topics, named entities, and parts of speech. Second, they display the extracted information with visualizations like word clouds, node-and-link diagrams, and lists of word contexts. Such systems make patterns of style, form, and theme visible, and interpretable by people.

However, literature study is a form of sensemaking (P. Pirolli, et al. 2005): a cycle of reading, interpretation, exploration and understanding. As useful as they are, current digital humanities text analysis systems leave the exploration and understanding part of the cycle unsupported.

The WordSeer project (A. Muralidhara, et al. 2011) is an effort to create a sensemaking environment for literature and language study. Like other systems for the humanities, it has search and visualization capabilities, but it also supports sensemaking activities like collecting and reorganizing information, exploring related words, finding frequent phrases and similar passages of text, and annotating, collecting and tagging items. The system has been under development since 2010. Recently, it was used to produce successful analyses of Shakespeare’s plays (A. Muralidharan, et al. 2012) and North American slave narratives (A. Muralidharan 2012).

To uncover areas for improvement, WordSeer was field-tested at the University of Calgary in the Spring 2012 semester. Students in the undergraduate Shakespeare class ‘Hamlet in the Humanities Lab’ ( M. Ullyot, et al. 2012) spent a few weeks becoming familiar with WordSeer along with four other computational text analysis tools. Then, during the rest of the semester, they used the tools to analyze a topic of their choice within an act of Hamlet. The students recorded their experiences through weekly posts on the class blog (http://engl203.ucalgaryblogs.ca/).

An analysis of their posts revealed four common ways of using digital tools that were not supported well:

- 1. Comparing two or more visualizations side-by-side or referring to multiple tools simultaneously

- 2. Narrowing down analyses by metadata, such as (in Shakespeare) a particular speaker, act, or scene.

- 3. Investigating a group of words together.

- 4. Getting ideas for a new search or analysis based on the results of a previous one.

WordSeer had limited, roundabout support for these activities. For example, Activity 1, comparisons: it was technically possible to compare two visualizations — but only by opening a separate browser window, navigating to the WordSeer Shakespeare website, and re-typing the search parameters for the second visualization. Activities 3 and 4: investigating groups of words, or performing new searches based on previous ones, required manually typing in long search queries, and Activity 2 was entirely impossible.

At this conference I will demonstrate a new WordSeer, completely redesigned with the above activities in mind. Instead of a separate web page per visualization, the application now mimics a desktop environment, with different visualizations opening up in “windows”. In the following figures (Figure 1-Figure 4), I briefly explain how the new tool supports the above activities.

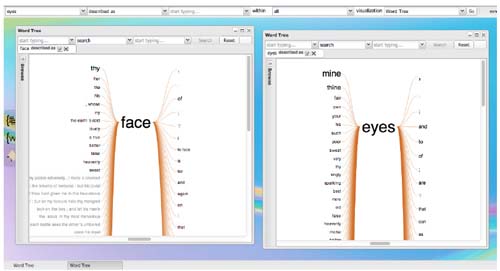

Figure 1

This figure shows WordSeer's new desktop environment, featuring a top bar for queries, a sidebar for collections, and multiple windows. Activity 1, comparison and reference, is much easier because the top bar preserves search parameters. For example, comparing the word tree for “face” with that of “eyes” above only requires changing a single word between queries.

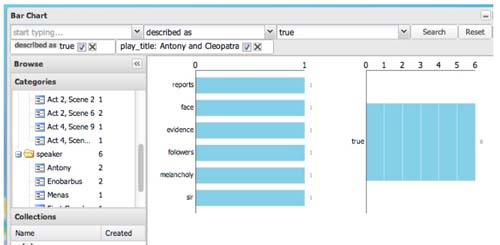

Figure 2

Metadata filters can be used to restrict analyses to relevant subsets, directly supporting Activity 2. For example, this figure shows how, to find all words described as "true" within Antony and Cleopatra, or to further restrict the search to individual speakers, users simply have to select the relevant categories from the browsing menu.

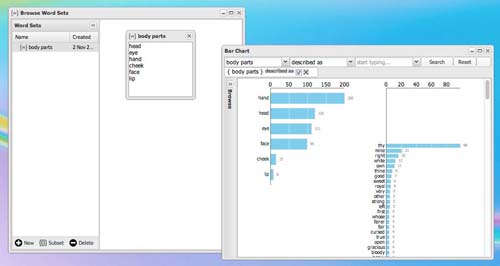

Figure 3

For activity 3 (investigating groups of words together), WordSeer has a new word sets feature for creating groups of words. These sets can be used as search queries, and updating the set with new words automatically reflects itself in the new query. For example, this figure shows how word set called “body parts” containing “head, eye, hand, cheek, face, lip” can be used as a grammatical search query (for “body parts” described as ___).