An Environment to Support User-Structured Digital Humanities Sources

July 18, 2013, 13:30 | Short Paper, Embassy Regents F

When building digital environments that provide suitable tools for scholarly research, there is a design tension between being generalisable and configurable: purpose-tailored tools only work with specific subjects and objects, while generalised tools can be difficult to use for a specific subject and object. However, there are meta-Use Cases that traverse many disciplines, and it is possible to build tools to support these within in a single hosting environment. In this paper we describe a hosting environment, CRADLE, that is configurable and generalisable.

At An Foras Feasa we repeatedly faced the same meta-Use Cases; researchers wished to create digital versions of their source-system (which might either be a single source represented by components within the system e.g. a manuscript of page-components, or multiple sources connected together, e.g. an archive of diverse materials [1] ) that were reflective of their personal theoretical perspective, provided tools for investigation, and permitted personal and community re-use. This extended to researchers who wished to use the digital source-system to support their teaching remit and to others; allowing them to reinterpret and repurpose hosted digital source-systems to create a digital version consistent with their own theoretical position. This implied that any solution would need to be able to handle multiple, configurable, versions of a digital source-system, and multiple metadata descriptions of any single component within the source-system.

CRADLE (collaborate, research, archive, discuss, learn, engage) was designed as a general software solution to support the hosting of multi-modal Humanities sources, discourse and learning resources. CRADLE has been designed to provide support for a variety of theories and interpretations of source collections. In particular, the general, but sophisticated, creator-user can configure multiple structures for their collections, and also describe multiple versions of each source-object within the collection. Furthermore, it is possible for other users to repurpose and reconfigure those source-objects to suit their own perspective upon them.

In the following fictionalised scenarios, we provide an example of how CRADLE supports this multiplicity of representation. A post-doctoral fellow with the Institute, Jane, is a professional editor, researcher and lecturer. She wanted to create a digital critical edition of an old Irish tale, originally extant in three manuscripts, so that she and her students could undertake research upon them. The digital surrogate object was composed of high-quality images of the manuscripts, their diplomatic transcriptions in XML documents, her edited best-version critical edition in XML, and an english translation of the critical edition. CRADLE provides a comparison panel to show any two of the three versions at a time(figure 1). When examining text, the XML versions are rendered, and equivalent passages across image or text versions can be located. Other tools are available to her and are briefly described further on within this paper.

Figure 1.

The CRADLE comparison panel for digital critical edition components.

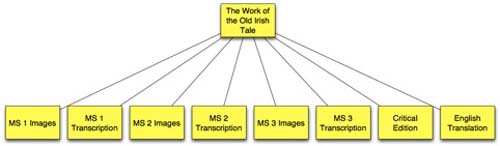

Let us now examine the multiplicity of the structures and descriptions that underlie Jane’s version of her Irish Tale. Importantly, Jane self-consciously considers herself to be building a Digital Critical Edition, not a representation of the real work, within CRADLE. She holds that the XML diplomatic transcriptions are inherited from the extant manuscript, not an abstract work. As such, they are less authentic than the manuscripts. Furthermore, she does not consider the images of the manuscripts to be surrogates for the original manuscripts because they have different materiality. Each of the objects is described in metadata, but the images have two descriptions: one for their manuscript-self (in TEI), and one for the digital-image-self(in VRA). Thus, she would describe and arrange all of these objects in a hierarchy as shown below.

Figure 2.

Jane's personal view of the structure of her source-system, a digital critical edition.

Another researcher and lecturer wants to (re-)use the source-system. Contrary to Jane, Steven believes that all extant versions, including the XML and the translation, have the same scholarly merit and that no single one is more authentic than another. For him, all of the versions, including the XML documents, are children of a single, parent, abstract work. Steven wants to use CRADLE to describe this actual work, not the digital version of it. Therefore, he wants the manuscripts to be fully represented by their digital images. Steven wants to be able to explain this to his students, and then to examine the tale from his own scholarly perspective. In CRADLE it is possible dynamically redefine the spring-graph-displayed relationships between the components of the digital critical edition in a personalised user space ("My Collection"). He can also redefine the metadata description associated with the images — while Jane had associated two metadata descriptions with the images (VRA for the image and TEI for the original manuscript page), he only wants to describe the manuscript page because he is using the system as if it really were the work. The structure of this system follows:

Figure 3.

Steven’s personal view of the structure of Jane’s original source-system.

This configuration and reconfiguration of editions, in particular, along previously undefined lines and based on personal interpretation is a direct response to calls from Eggert (2009) and Burnard (1999), among others, for what Burnard terms “an uncritical edition”, and while operating at a higher level of abstraction than that to which he referred, it nonetheless allows for user-driven and defined editions. In this way, it extends the conceptual work already started in projects such as Wittgenstein's Nachlass: The Bergen Electronic Edition (BEE), which allows users to manipulate the edition within the online environment, but through predefined and encoded versions. Gabler’s recent call for a means to navigate the “pyre of humanities objects” using the tools of digital humanities to “allow us to relate, or to model, their relationships — to inscribe the relations and correlations into the materials we digitise” (Gabler, 2012) is also answered with this type of approach. It is possible to use it as a direct model of the source or system, where the reader-user suspends their disbelief and operates within the collection as if it really were the real-world collection, or as an indirect model, where the difference between the real-world collection and digital collection is made obvious and described in detail.

Existing repository solution software, such as FEDORA or Hydra, support the hosting of sources and the many configurations such a system would demand, but they require significant expertise to operate. Other digital library solutions could support multiple representations of sources, but do not supply source-specific tools for detailed investigation, such as the comparison panel; nor do they support dynamic source structural re-configuration in a way that is open to general Users to manage. As far as the authors are aware, no existing systems allow for the direct association of discussion forums or learning resources with sources within a single environment. CRADLE was therefore designed to sit on top of existing repository software(currently FEDORA), provide an intuitive front-end to users wishing to create complex digital versions of their source systems, and provide tools for the research-driven interrogation of those, along with teaching and learning support.

Below it is possible to see the configurable relationships within the test collection used during development of CRADLE; the 1950s newsreel Amharc Eireann Archive, held in the Irish Film Institute.

Figure 4.

Examining the relationships between the newsreel sources within an archive collection.

Metadata describing structure, such as TEI or VRA, can be interpreted by CRADLE and used to generate the relationship graphs. Here, two sample newsreels have been configured as a collection, and that collection is a child of the parent digital Amharc Eireann Archive object. On the left, the source is depicted. On the right, its relationships are viewed in a spring-graph of objects, showing their associated learning resources (a single annotation) and discourse (35 discussions). Once the new user’s personal collection has been created (using the ‘Create New Collection’ option, in the top right of the image), it is the relationships within these graphs that can be clicked and edited to redefine the relationships. The creator-user can then control permission on the new collection to share it with colleagues, students or teachers.

Multiple perspectives on the nature and structure of humanities sources can be accommodated within CRADLE, even for the same real-world objects. Using CRADLE to create models that not only describe our sources, but represent their structure in a manner that is manipulable, reconfigurable and shareable allows researchers to define their own understanding of their material, while also making that material usable to a much wider community. Along with the many source-specific tools, and the provision of a hosting environment for learning resources and discourse associated directly with the humanities sources, this provides a valuable solution to those active in the area of digital humanities research.

References

Notes

1. These distinctions are loosely based on the VRA view of collections, objects and images.